DAVID BRINKLEY

11 Presidents 4 Wars

22 Political Conventions

1 Moon Landing

3 Assassinations

2,000 Weeks of TV News

And 18 years of Growing Up in North Carolina

By Billy Cone and Brooks Preik. Photography by Brownie Harris.

He has dined with presidents, reported the comings and goings of royalty, talked backstage with eminent actors, shaken hands with celebrities in all walks of life and brought the stories of the famous as well as the not-so-famous to the attention of the world. He has reported on three major wars and every military conflict since World War I. He journeyed to Cape Canaveral for a stirring account of the landing on the moon, and he was a powerful presence at the first nationally televised political conventions.

A legendary figure in the annals of television, Brinkley fashioned the mold from which network news reporting was patterned. In fourteen years before the cameras, he and his friend and colleague, Chet Huntley, won every major broadcasting award as well as the hearts of the entire nation hosting the Huntley-Brinkley Report. From the halls of the White House and the nation’s Capitol to the Great Wall of China, David Brinkley has walked side by side with the greatest statesmen of this century.

The barefoot boy who stood on the banks of the Cape Fear River, watching ships from all over the world bringing their cargo into the port at Wilmington, North Carolina, must have dreamed even then of faraway places and adventure. But it was the telling of tales that fascinated him most. From the time he could first remember, Brinkley wanted to be a writer.

Attributing much of his success to “more than my share of luck,” Brinkley readily admits it was the encouragement of a favorite high school English teacher that eventually steered him toward a career as a journalist. Mrs. Burrows Smith helped get him his first job with the Star-News through a school program of cooperative education with local businesses, and she inspired in him the self-confidence he lacked. His academic skills were honed at the hands of the local librarian who became his mentor and his friend, and he developed an insatiable desire for reading that persists to this day.

During World War II when many of his friends were in the armed services, Brinkley enlisted in the Army. The misdiagnosis of an army medic earned him an unwanted, yet honorable, medical discharge, and, in the process, saved his life. He returned to his job at his hometown newspaper until a particular bit of clever, humorous reporting—of a kind that would become his trademark—brought him national attention and a job offer from UPI. In his early twenties, Brinkley made it to Washington and a position with NBC News, earning— what seemed to him at the time—a fabulous sum of money.

David Brinkley had an uncanny knack for the news and soon he was one of the most popular journalists in the country. He set the standard for television broadcasters, learning on his own by trial and error in a new, rapidly developing industry that came with no directions. As a White House correspondent for NBC, Brinkley watched American history unfold under the leadership of FDR and his successor, Harry Truman. He grew to respect Truman’s honest sincerity and his skill as a politician. Brinkley was there through the two terms of Dwight Eisenhower, and from John Kennedy to the present, he has been on a first name basis with every president. Kennedy and his family were personal friends of the Brinkleys and reporting the tragic death of the young president and the events that followed was one of the most difficult assignments of his entire career.

In private meetings with Lyndon Johnson he expressed his opposition to Johnson’s Vietnam policy. Brinkley abhorred “Dick” Nixon’s paranoid and underhanded tactics, but he enjoyed the company of the genial, movie star president, Ronald Reagan. It was President George Bush, a man for whom he has the greatest admiration, who presented Brinkley with the Medal of Freedom. This award he prizes more than all the rest. Following his years at NBC, Brinkley accepted an offer and an exciting new challenge with ABC, where he achieved even greater fame with his Sunday morning program of news commentaries and interviews. This Week With David Brinkley put the ratings for ABC over the top. The talents of George Will, Sam Donaldson, and Cokie Roberts coupled with the experience, candor, and wry humor of David Brinkley were an unbeatable combination.

In recognition of his outstanding achievements in television, Brinkley has received ten Emmy Awards and three George Foster Peabody Awards. Brinkley has faced personal tragedy along with his triumphs. The death of his father when he was only eight years old had a tremendous impact on his life. After many years of marriage, he was divorced from his first wife, Ann, and was deeply saddened some years later when she died a cruel death from Lou Gehrig’s disease. His last surviving sibling, Mary, who had lived for years in Washington and was Senator Joseph McCarthy’s secretary, fell victim to Alzheimer’s before her death and eventually could no longer recognize her brother.

In spite of these and other adversities, his life has been marked by moments of great happiness. In 1971, David Brinkley met the love of his life—a beautiful, accomplished young woman, Susan Benfer — at the home of his friend and fellow newsman, John Chancellor. Their wedding was celebrated in a gorgeous, historic Williamsburg mansion with a host of family and friends present.

Brinkley has been enormously proud and gratified to see his three sons follow in his footsteps as award-winning writers. Alan is a history professor at Columbia University and the winner of the American Book Award; Joel, a correspondent for some years, won a Pulitzer Prize, and is now an editor at the New York Times; and Brinkley’s youngest son, John, is also a writer—for the Scripps-Howard newspaper chain. Alexis, his only daughter, whom he adores, graduated from one of her father’s Alma Maters, the University of North Carolina in Chapel Hill, (the other was Vanderbilt University). She holds a master’s degree in special education.

In his autobiography, David Brinkley, A Memoir, Brinkley says of his life and his family, “With all this, I am blessed beyond anything that in my days in Wilmington, North Carolina, I could ever have expected or even imagined. Credit it all to luck, modest talent and chancing to be in the right place at the right time to start modestly in a new and promising industry, television, and to grow with it as it grew to its overwhelming presence today.”

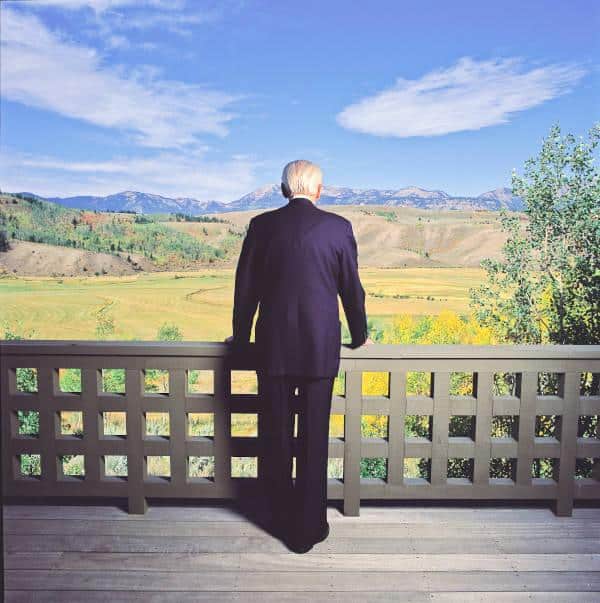

On September 12, Brownie Harris and Billy Cone flew to Jackson Hole, Wyoming, to meet with David Brinkley for a photography session and an interview. The following conversation between Billy Cone and David Brinkley took place at Mr. Brinkley’s home in Wilson, Wyoming, on September 13. This article and these photographs are presented as a tribute to Mr. Brinkley, a much admired and respected native son of North Carolina, in honor of his long and distinguished career in journalism.

You were born and raised in Wilmington, North Carolina, and you have lived most of your life in Washington, D.C. Are you planning to make your home in Wyoming a permanent one?

No, we’ll be moving to Houston in October. I am working on a fourth book— Fifty Years in Washington— and if I may say so each of the previous three was a best seller. There are no research facilities here. We’ve been living in a small house, and some time ago my wife, Susan, and I agreed that we needed more room. We also wanted room for our kids to come to visit, so we began thinking about buying a larger house. The question then came, buy a house where? One suggestion we made to each other was Wilmington, because we still love the town. We have good friends there and we love the beach. My daughter, Alexis, in the meantime, had married and moved to Houston, Texas, so we finally decided on a house there. It’s a much bigger house—plenty of room. Houston is a very nice place, and we have many good friends there. It has good research facilities, great restaurants, and it’s easy to get from there to New Orleans, which is one of my favorite cities.

Would you share some of the highlights of your early years in Wilmington with us?

Well, there are many. I lived at 8th and Princess, but the house is no longer there. I went to New Hanover High School. I had more luck than I am entitled to. I’ve always wanted to be a writer, and my family thought I was crazy because they didn’t think that I could ever make it. My English teacher, Mrs. Burrows Smith, who was a wonderful, wonderful lady, noticed I was in the library all of the time reading and doing research and so on. I showed her some things I had written. After a time she said, “David, I think you ought to be a journalist.” Sounded good to me —anything was better than sitting in a classroom. They had a program called cooperative education, or something equally silly, and it allowed you to leave school early and go to work for nothing in some local business. I chose to go to work at the Star-News. The afternoon paper was edited by John Marshal, but it’s gone now. On the morning paper I worked for Al Dixon, who was the managing editor, and we became close friends and remained so until he died. And that’s where I learned my trade pretty much, by working for those two guys, who were really quite good.

Your English teacher helped you in your decision to become a journalist. And you’ve mentioned the influence of those at the newspaper. Was there anyone else who made a difference in your life during that time?

I got lucky again. I’ve always been very curious and book-oriented, so I began using the Wilmington Public Library. I ran into the librarian there, a great, grand wonderful lady, whose name was Miss Emma Woodward. She found I was in the library everyday, and she took me over and tutored me. That’s really where I was educated. I learned more from her than anyone. I’d spend all afternoon with my own little tutor. I am eternally indebted to her. I’ve kept on learning ever since because I read all of the time, but still that’s where I got started, in the Wilmington Public Library.

What was the very first paying job you ever had?

Working in an A&P store on Saturdays. It was the beginning of so-called self-service, which is a nonsensical term. A lady would come in with a piece of paper with the grocery list she wanted. I was told to ask for the list so I could get it all together and get her in and out faster. But she wouldn’t give it to me. She’d say, “I want a can of peas,” and I would have to run all of the way to the back of the store to get a ten-cent can of peas and put it back on the counter. Then she’d say, “I want a can of corn,” which was right beside the peas. I could’ve gotten both the first time, but I had to run all the way to the back again. We sold what they called tub butter back then. You had to spoon it up with a wooden thing and put it on a balance scale. I always cheated a little bit and gave the customers a little extra, particularly if I felt sorry for them for some reason.

When you worked for the Star, what was the strangest story you ever covered?

The strangest story…well, it was sort of a funny one. I heard that a woman on South Fifth Street said that she had a century plant that bloomed only once in a 100 years, and it was going to bloom the following Tuesday night. I believed her. So on Tuesday night I was there. By that time, the word had gotten around and a crowd was gathered in the street. The fire department called out its searchlights to light up the street. People on South Fifth Street began to complain about the crowds in the street, all of whom kept coming in, asking to use their bathrooms. And then of course, the plant did not bloom. I later learned a little more about it and it was never about to bloom! Anyway it was a sensation, and I wrote it up and played it for jokes and laughs. After that, Lamont Smith, who was the editor of the Star, offered me a regular job. And the rest is history, I guess you’d say.

Didn’t you also work at Lumina, the big pavilion that used to be on the oceanfront at Wrightsville Beach?

I did. Every summer I had a job there changing light bulbs on the Lumina sign on the roof. If I remember correctly there were 126 light bulbs and almost every night ten or twelve burned out. So I had to climb up there with a basket of sixty-watt bulbs and replace them. I also worked as a soda jerk. And did I tell you about burying the whiskey in the sand?

No, tell me.

Well the young blades would come to Lumina and bring whiskey. They would have a pint of whiskey on their hip in a flask. I was running one of those soda stands on the Lumina dance floor, off to one side. You probably don’t remember that. A lot of them would come to me and give me the flask and ask me if I would keep it for them until intermission, because they didn’t want to be on the dance floor with a big bulge in their pocket. I said I’d do it, but I’d have to charge them 50 cents. Most of them paid, and I don’t know what ever happened to the money. I didn’t get it. A few of the cheapskates figured they’d bury their liquor flasks in the soft, deep sand surrounding Lumina. They thought they’d go back at intermission and get it and save the 50 cents. The tragedy came when they couldn’t find it in the sand. You’d see these guys out there in their good clothes, down on their knees, looking for their liquor bottles, which they never found. In the morning Tidewater Power Company would have a couple of fellows go out and rake the sand just to keep it clean. They found bottle after bottle buried in the sand. Of course they kept them. Those jobs were always easy to fill.

Can you tell us the story about Dry Pond and how it changed your life?

Dry Pond was one of the poorest neighborhoods in town. It was rough and tough and I never went there. Doc Hall’s drugstore was on the edge of Dry Pond, and he was the unofficial mayor. In 1940, I enrolled at the University of North Carolina but changed my mind. I decided I couldn’t sit out the War with all my friends all going to the Army, Navy or something. I volunteered and the company I was in— Company 1 of the 120th Infantry—was composed almost entirely of men from Dry Pond who had been in a National Guard unit that was absorbed into the regular Army. Doc Hall’s son, Mike, was the first lieutenant. Later I got shipped to Fort Jackson, South Carolina, where I had the greatest piece of luck in my life. The Army medics said I had a kidney problem, which I did not, still don’t, and never have had. I was honorably discharged for physical reasons. It was a mistake on the part of the Army medics, but I now know that it saved my life because in 1944, when my company landed in France, bombers from the Eighth Air Force flew over carrying bombs intended for the Germans. The cloudy weather and dust from earlier bombings kept them from finding their targets. They had to drop the bombs anyway, and they exploded by mistake on the 120th Infantry’s Thirtieth Infantry Division. It was a terrible disaster. Of the 250 men, 245 died. Nobody in Wilmington ever knew that, because the Army had censorship then, and they covered it up.

What did you do after you were discharged?

I went back to the Star, got my old job back and was working there when everybody in the world was being drafted. I had been in and out and was draft-proof from then on, and people began calling and offering me jobs.

Why were you chosen to deliver the first five-minute news program for the Wilmington radio station?

Because I had had some experience. I was young. I was a quick learn. I had a real, deep profound interest in the news, and they needed somebody to read news on the air. It was during the War. They could no longer get by without news. Until then they had none. The station was then called WRBT. I was still working at the Star-News, and Rinaldo Page, the paper’s publisher, offered the station manager, Dick Dunlea, five minutes off the AP wire every day, written and read by me, for no extra pay, of course. Some years earlier I had won an essay contest on the topic, “What WRBT Means to Wilmington,” sponsored by the same station. My prize was five dollars.

And then what happened?

I got a call and a job offer from United Press, which was a wire service, now defunct, and I moved to Atlanta. Then the UP moved me to a little office in Nashville, Tennessee, writing news to go out on the UP wire, and they appointed me manager. I was twenty-two. Later they moved me to Charlotte. A year later I began to get calls from newspapers and others. NBC offered me more money than I ever knew there was in the world, so I went to Washington to work for NBC News. One thing led to another. I was fairly good at it and I wound up staying there 14 years doing a program with Chet Huntley. After Huntley died, I went to New York and worked awhile. They sent me back to Washington, and I was doing some pretty good work, particularly on politics. Then they couldn’t find anything else for me to do, so I took a job at ABC. They offered me even more money. Money talks, apparently. Next thing I knew, I was running a Sunday morning program called This Week with David Brinkley, which became a big success and swept all of the competitors off the air. I worked there until I decided to retire. I didn’t need to work anymore, so here I am.

When did you have that apartment in New York that was so amazing?

It was a four-bedroom apartment, just for two people, paid for by NBC. They had an outrageous amount of money and they also gave me —I’m almost ashamed to say this—a chauffeured limousine.

What year was this?

I don’t know…sometime in the 40s. Then they later moved me to an apartment in a brand new building, the name of which I can’t remember either. Super Luxury! Most of the people there were drug dealers, I learned later. The richest people left in the country lived there. And it was immediately across the street from NBC so I could walk to work. I was the object of much joking and rivalry among my friends at NBC. “You lazy S.O.B., you walk to work—the only one in the whole RCA building who can walk to work.” So anyway, that was that.

You were there at the beginning of television, one of the pioneers. What did you use as a guide to create a format for reporting the news in the early days?

I had to make it up because there wasn’t any guide yet. NBC’s Washington station, WRC, not the network, hired me and told me to run around town with a cameraman, pick up whatever little news item I could, take it to the film lab, have it developed, bring it in to the studio by about 5:00 or 6:00 o’clock and they could put it on the air at 6:30. I had a five or ten-minute news program and it was pretty bad, because there was no news to begin with, and we were not equipped to get it if there was. I had a cameraman, George Johnson, who went around town with a camera made by Bell & Howell. It had a hundred feet of film, which is good for about three minutes. One night he brought in two of the three stories I remember. One was about some kind of experimental testing on sheep, out of town, being run by the Agriculture Department, which I knew absolutely nothing about. He brought that in and we developed it. And the other story, this was in Washington, about a high-ranking, war hero who had died. Arlington Cemetery gave him the bugle call and the triangular flag and all that, and we covered that, which was legitimate news. In those years we were using 16-millimeter film which has holes down both sides. Sound film has a sound track on one side, and sprocket holes down the other side. If you are not careful and don’t know what you are doing, which is usually the case, the film will go into the projector backwards. That night I went into the studio to narrate the film, and the first thing I heard was the bugle call playing taps, but on the screen was a picture of a sheep. It was all very embarrassing, and I will hear about that for the rest of my life. The engineers didn’t yet know what they were doing. That’s the end of the story.

All this leads me to a question I’ve been dying to ask. What’s the funniest story you have ever covered?

I don’t know if this is the funniest, but this one was pretty funny because no one could ever explain it. I always tried to end my program on Sunday nights with a little humorous story from the news when I could find one. This report came in from some town in Africa where the police had arrested the driver of a tiny car. He was an African male, driving a Volkswagen Bug. Inside it he had 12 goats, and all of them wearing men’s underwear. And then they found out all of the goats were pregnant. And I had to end the story by saying, “Don’t ask, I don’t know!”

I have to ask. Who is the funniest person you ever interviewed?

Johnny Carson. He was a good friend. I spent some time with him. He’s laid up now and not well. You just reminded me, I have to check up on him. Johnny Carson is the funniest man…and Jack Benny. I never knew him, but I knew him on the air. He was damn funny and a few others.

You have an amazing talent for making almost any event sound like a great happening. How did you acquire this skill?

I’ll be the first to deny that I have it. I don’t have any such talent. The talent I do have and have worked on very hard is clarity ? to tell the American people what has happened in the world. It is the first they have heard about it. They don’t know all of the details. You must make sure that you make it clear. Write it in such a way that it is not cloudy and uncertain and so you don’t leave people saying “what did he say, what was that?” I tried never to do that, and it worked well, and I got to be pretty successful on television, mainly for that reason. I don’t have the ability to make small events look big. You can’t do that.

When did you realize your style of writing and speaking was so distinctive and popular?

Well I first learned and developed a so-called style on the radio, which I did long before television came about. On the radio, as on television, you have to make it clear to people who don’t know anything about it. Not that they’re dumb, it’s just that it’s something they have had no access to until you tell them. And so the rule for me was to speak clearly, never mumble. I hear people on the air today who should not be on because I can’t understand anything they’re saying. On any kind of broadcasting you get one crack at it, so you must be clear above all. If not, you’re wasting your time. You should be driving a taxi.

Who would you say influenced you the most in the delivery of your written words?

An announcer at NBC in Washington when I first went to work there named Don Fischer. He took a little time off to coach me. I had a southern accent, which I don’t think is all that bad, but anyway you can’t do it on the air. And he worked with me and coached me and helped me a lot.

How much of your success in life would you attribute to talent and how much to timing and luck?

Some of all three. I can’t break it down in percentages.

In comparing today’s reporting, which is often referred to as entertainment rather than hard news as in the early days, what differences do you see? Would you say that a lot of the news today is entertainment?

Well you can call it entertainment; it doesn’t have to be hard news. It can be something in between, which most of it is. Because the problem is simply this, anytime that you have a period of time set aside for you in which you are allowed, or asked, or hired, to give the news; suppose there is no news, and there are many days when there isn’t. Nothing of any importance at all. So you have to dig around, and dig around and find something that sounds like news, or looks like news, and you can’t get away with faking anything. It is very difficult. And it is true that people sitting at home expect something exciting every night. Well, we can’t make it up. Some have tried once in awhile. They always got in trouble. You can’t do it. So we had to put on all of this stuff, which we knew when we put it on wasn’t much good. It wasn’t terribly interesting and it wasn’t terribly important, but you have to fill the time with something. And so we get hanged for that and understandably.

You’ve known eleven U.S. Presidents. Could you tell me some interesting stories about any of them?

Mmm, that’s a tough one, because I’ve covered so many. I used to go to the White House when Lyndon Johnson was president, because he kept inviting my wife and me, and I never knew quite why, but he did, and when the President invites you, you more or less have to come. I finally got to know him well enough to say “Mr. President why don’t you end this Vietnam War, because you cannot win it. If you do somehow win it, you will not have won anything, and in the meantime it’s killing a lot of young, American men who deserve better. Why don’t you stop it?” And he said, “I will not be the first American president to lose a war.” And that was the only excuse he needed. And he also said privately, so I could not quote him, “If I end the war, the right-wing will tear me to shreds.” Which I think was wrong, but that’s what he said and he was the president. I put the same question one time to John Kennedy who was then the president and he said, “It’s this ridiculous domino theory that if one country goes communist, the country next to it will go communist.” I said, “I don’t believe it, do you?” And he said, “Yes, I do believe it.” And he was afraid communism would sweep the whole Asian land mass and he would get blamed for it. But they were both wrong.

So Johnson thought pulling out of Vietnam would have been losing?

Yes, and in a way it would have, because then the Viet Cong would have taken over everything and we would not have been there to stop them. It was a terrible decision. It was very hard to get it stopped. Finally we did. I say “we” did, but I didn’t have anything to do with it. Americans did. Johnson should have ended it and taken the heat and saved some lives. The Mall, which is a big green stretch down the middle of Washington, DC, is full of monuments to various wars, but the most emotionally disturbing one is the one to the Vietnam War and those who died in it. Unlike other war monuments, which are cold statues, this one is still kept up to date. It is a list of names of real people—people you might have known—who died in Vietnam. Very few, including me, are able to stand looking at the wall, reading all of those names, without tears. I can’t do it. It is so horrible—a monument that really tears you apart.

What do you think of the Nixon/Kissinger foreign policy toward Vietnam?

Kissinger is a good friend of mine, one of the… maybe the smartest man I’ve ever known in my life. We often discussed it, and I didn’t argue with him because he knew more about it than I did. And I don’t think he—and I’m sort of speculating here—thought we could ever win it, but he had Dick Nixon on his back all of the time demanding a victory so he could claim it and nobody, even the US Army could deliver it. The war sort of drizzled away in the end, until it became clear to everyone that it was no war worth fighting. You remember the picture when the people climbed on top of the American Defense Building in Saigon to get into the helicopter to fly away? It was a humiliating end for the Americans, but we, again, should have never been in it in the first place.

Put John Kennedy in context. How should history view the Kennedy presidency?

Well, of course, he wound up a figure of gross tragedy at the hands of that punk, Lee Harvey Oswald. John Kennedy was a Democrat and a liberal, and once you position yourself in the American society as a liberal or a conservative you gain some friends and lose others. He was very active in the field of civil rights and it may be that much of the country wasn’t ready for it. It’s hard to believe, but I think true, and I think history will remember him as an interesting president who did not turn the world over and who ended tragically.

Did you ever break up on television?

Yes. John Kennedy was a good friend of mine. And so was his family and my family. It was so sudden and so ugly and so nasty. That little son-of-a-bitch, Lee Harvey Oswald. Jack Ruby shot him. It was the only time a murder was ever seen live on television. The other network stole it off our air and used it without credit, but nobody wanted to argue about it.

What imprints did the Kennedy assassination and that of Martin Luther King have on American history?

A very distasteful imprint. A number of people phoned and wrote and stopped me in the street and said, you know we are no longer a civilized nation when things like that happen. I think it was a big disappointment and in the immediate aftermath there was a fear that it was all coming apart. It was just a perfectly horrible time and I was on the air throughout. People crowded around waiting to hear something; that was before anyone knew if Kennedy was dead or not. When the news finally got out that he was dead, people cried in the streets. Like all tragedies, it gradually faded away, and I don’t know that we learned anything from it of any real value.

Why do you think America had such a love affair with Ronald Reagan and Bill Clinton?

I particularly liked Ronald Reagan. He never pretended to be any high-flown public hero. He was a very pleasant, likable person. There was no artifice about him. He sounded very patriotic and talked about the “shining city on the hill”, which never quite existed, except in myth. If you had known him, you would have liked him, plus the fact that he put through the last tax cut we have seen in God knows how long. When Clinton came in he put them all back on. And Clinton became popular because the economy turned out to be really excellent and the country was booming, getting rich and making money.

What would you say was one of your most memorable experiences with a president?

It was toward the end of World War II. Joe Stalin was making ugly noises and moves in Russia, and nobody knew exactly what he was up to. Winston Churchill, who was still the Prime Minister of Britain, was very much worried about what Stalin had in mind. He called Harry Truman, who just after Roosevelt died had become the President, and said he was afraid Stalin was making some really dangerous moves. We were removing our troops from Western Europe as the war had ended. Churchill didn’t quite know what to make of Stalin’s actions, and he wanted to talk to Truman about it. So Truman said, come on over, and he came. And Churchill was invited to make a speech in this country, and there was some debate about where the speech should be because it would be an historic event. Truman invited him to come to a little college in Fulton, Missouri, Truman’s home state, and to make a speech there. That’s roughly in the middle of the United States. Truman met Churchill in Washington and put him on the presidential train, in the presidential private car, which had been Roosevelt’s before Truman took it over. It was a railroad car fitted up with beds and everything; it was called the Ferdinand Magellan. It was an armored car with all kinds of fixtures put in for Roosevelt’s use in case of an accident, because he was crippled and couldn’t walk. It would have allowed him to get out of the car. A few reporters went along, and I was one. From Washington across the country to Fulton, Missouri, was a two-day trip. Along the way, Churchill said to Truman, “Mr. President, I understand that in this country you play a lot of poker.” Truman said “Oh, yes we do, we play a lot of it, and if you would like to play a game we’ll have it now.” I think there were six of us in the game, and they had a porter on board in a white jacket and he got out the poker chips and white coat and so on and set up a table and got out the cards, and we started playing poker. Churchill said he knew the game, but it turned out he didn’t know it very well; he began losing steadily. Truman interrupted the game so Churchill could go to the bathroom. I guess that was it, and while he was out, Truman said to the others of us in the game, “Listen, this man’s oratory saved the western world from Hitler, we do not want to take his money. So while he is out I am telling you what to do, let him win.” That was the President of the United States ordering us. We only had one choice. That was to obey. We all let Churchill win, and that was it.

That’s a great story. Thank you. I’d like to ask you just a few more questions. I think our readers would appreciate hearing your opinions on these important issues.

As a strong advocate of civil rights all your life, you have known and worked side by side with great civil rights leaders; can you comment on this?

I was the first one to put Martin Luther King on the air. NBC had assigned me with a film crew to travel around the South. We were then waiting for the Supreme Court to rule on Brown vs. the Board of Education, which would mean the end of school segregation. And the vote came as expected and the cities and counties and states were no longer allowed under the law to have segregated schools. And it caused riots in the South. I got stuck in the middle of some of them and it was quite dangerous at that time to have an interview with David Brinkley.

Was it right for the US to drop bombs on Hiroshima and Nagasaki. I know that’s a hard question to answer, but what would you say?

I find it an easy question to answer. Yes, it was right. The Japanese started the war. I’ll tell you a little anecdote that happened in Wilmington. When I was a very young boy, a teenager, ships came up the Cape Fear River. I don’t think they come up to Wilmington much anymore because of the new terminal, but this one was tied up at the foot of Walnut Street. They were loading aboard wooden bins about a foot deep and about six feet long, full of junk: old automobile engines, auto wheels, old pieces of metal junk. I watched this for a few minutes, and there was this sailor loafing around on the deck. I said to him, “What is this junk; where is it going, and who wants it?” He said, “It’s going to Japan so they can melt it down and shoot it back at us.” That was my first news of Pearl Harbor, though, of course, at the time I didn’t understand it. I got a big scoop and didn’t know I had it on the Wilmington dock at the foot of Walnut Street.

Should the Vatican have done more to help and assist Jews during the Holocaust?

I can’t answer that, because I don’t know what the Vatican could have done. I’m a Presbyterian, and I am not well versed in the rules of the Catholic Church, for which I have the highest respect; many of my good friends are Catholic. I don’t know what options were open to the Pope. He couldn’t order it stopped, because the Nazis were all crazy, as we know. So far as I am aware, most of the Holocaust was not known outside of Germany. I didn’t know it until the War was well along. And what the Vatican could have done, I do not know. If it had the power to stop it and did not, I think it would have been horrible. But I’m not sure it had that power. I’ve had many Catholic friends whom I’ve discussed this with, and they all agree that the Vatican should have done something, but no one has ever explained to me what it might have done that would stop the Holocaust. And to this day I can’t imagine. I don’t think even the Germans‹the Catholics in Germany could stop it once it got started.

Why did we lose the war in Vietnam?

Because we had no real purpose in being there. We were there to bail out the French, whom we had bailed out once before, and then we bailed them out in War World II. This was a war between France and the Viet Cong. We were trying to be a nice, friendly neighbor and as a result the French hated our guts and still do. They look down on us as barbarians, which is reversed I think. They think we are uncivilized and we don’t eat the food they think we should eat. It’s a lot of damn nonsense, but there it is. And why were we in it did you say? Because Lyndon Johnson and John Kennedy wanted to win the war, but there was no war to win. It wasn’t really a war. It was a guerrilla fight, which we were not really equipped to win. They used to explain it to me by saying, well these people, the Viet Cong, they’re tiny people; they’re not strong; they wear sandals made of cut up automobile tires; they have no Air Force. I felt like saying, in that case, why haven’t we defeated them already? But we were fighting in their territory, in their swamps, a long way from home. It was a disaster that could have been avoided.

Some of the interviews you have done have been about events that have changed the world. Did they ever change your life in a significant way?

I know what you’re getting at. It wasn’t an interview, but Huntley and I were sent to Chicago to cover the political convention. It was the first one I had ever covered or maybe the second I’m not sure. In any case, I saw this as a big opportunity and I did a lot of particular, very special studying in advance, writing everything down in a notepad. I used these notes I had compiled over hours and hours beforehand, and the day after the convention opened, I got the most favorable review from the New York Times’ television critic that anybody ever has had in his life; it really put me in business, because the New York Times is regarded in New York as the “golden fleece.” When the Times praised me, I suddenly became serious and important and worth real money.

What does being a Southerner mean to you?

It means a great deal to me. I’ve always loved the South, still do, partly because the people in the South are nicer, more friendly. Wilmington is a very sweet, little town, or a little city, bigger now, I understand. I made some wonderful friends there, and I still have those, the ones still alive. I’ve outlived most of them. I loved Wrightsville Beach too, and the home we used in the summers.

What do you miss most about the South when you’re not there?

The South itself, the people, the friendly attitude that I was used to, in the little town where I was born and grew up.

You have received many accolades and honors in your career as a journalist. Which single honor means the most to you and why?

I guess the Medal of Freedom, which is the highest honor this country can bestow. It goes to very few people. A maximum of, I think, three or four a year. President George Bush gave it to me some years ago. It hangs on my wall. It’s a beautiful medal with a ribbon, if you are ever inclined to put it around your neck, which I never have been. Only the President can award it, no one else. Congress can’t give it to you. The President gives it to you. And that’s the only way to get it. I am very proud of it.

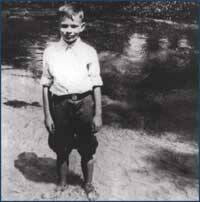

A young David Brinkley

– in knickers

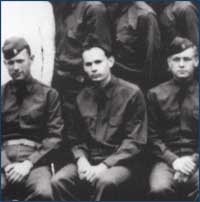

Sergeant David Brinkley,

120th Infantry

© VisitWilmingtonNC.com™

Editor’s Note: This article appeared in Capturing The Spirit Of The Carolinas.

No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, mirroring, or otherwise, without the prior written permission of the publisher.