Dean Smith

The Reluctant Legend

By Scott Czechlewski. Photography by Brownie Harris.

Four years after retiring, Dean Smith still holds the title as the most successful college basketball coach in history. His thirty-six University of North Carolina teams won 879 games, seventeen Atlantic Coast Conference regular-season titles, thirteen ACC tournaments and two national championships. Not to mention that he coached the 1976 Olympic Men’s Basketball Team to a gold medal. So why doesn’t Dean Smith feel he should be in the Hall of Fame?

In my first moments in the presence of Dean Smith I witnessed something few people have ever seen: the Coach being coached. Of course, this wasn’t on a basketball court. That truly would have been an unlikely event, maybe even unheard of.

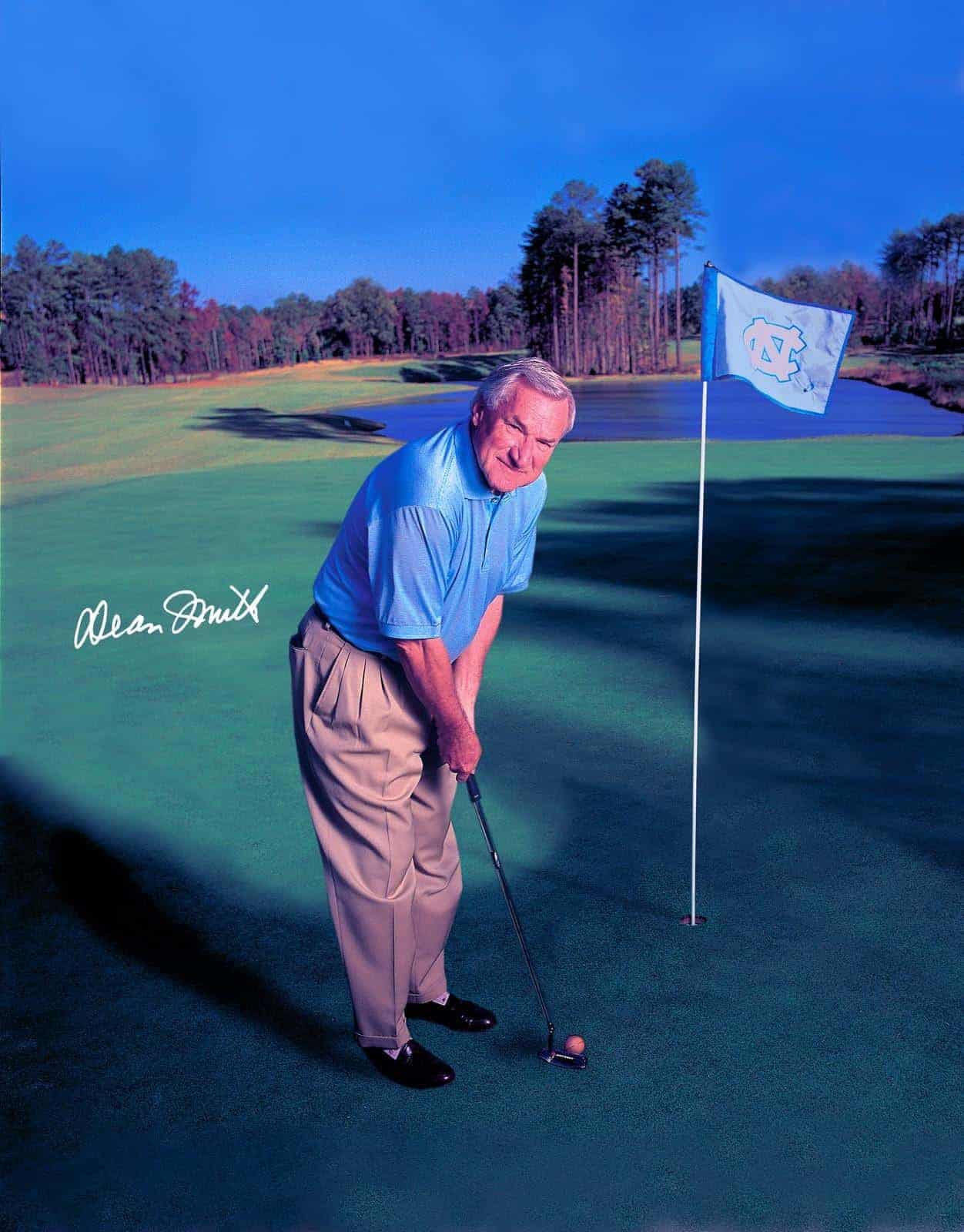

This occurrence took place on Finley Golf Course in Chapel Hill on a breezy Indian summer morning on the equally beautiful green for the fifteenth hole. Coach Smith was posing with a putter in his hands as Brownie Harris snapped off a reel of photos, hoping to capture the perfect shot for the cover of the magazine. The strengthening sun peeked over the pines, causing Dean to squint and Brownie to instruct him on several occasions to open his eyes.

It was ironic, since that is exactly what Coach Smith spent his entire career doing for the basketball community and fans across the country. He was responsible for opening many eyes on diverse fronts, from civil rights issues to innovative ways to play the game. His signing of Charles Scott desegregated Carolina basketball and made Scott the first black player at a predominantly white university in the Deep South. Smith showed that control, patience and discipline won games by instituting innovative techniques like the Four Corners, which resulted in fundamental rules changes to the game. He stressed the importance of teamwork by requiring players to point to teammates who had made an assist to share the credit for a score, a common practice at all levels of play today. But above all, he opened the eyes of fans and other coaches by standing by his convictions that winning isn’t everything.

I suspect many of Smith’s players had their eyes opened as well, not simply by his wealth of basketball knowledge or his ability to impart it in a disciplined, congenial fashion, but by the nature of the man himself. For Coach Smith has that special ability to act as father and friend, coach and student. It may well have been this aptitude that coaxed great performances from average players and turned great players into superstars.

As we sat down to talk, it quickly became apparent that Dean Smith basketball had never been about a stack of highlighted stat sheets and players reduced to hasty X’s and O’s scratched onto chalkboards. For Smith, those X’s and O’s had faces and names, families and aspirations. One of the first things that he chose to tell me concerned a phone call he’d received a couple weeks earlier from former player Scott Williams, Class of ’90. Williams had called to relay the news that he may have to retire from the Milwaukee Bucks due to a back injury and to pass on an update on his new son, Benjamin. The baby was premature, but doing fine after three months. A week later Smith read that Williams was traded to Denver, where he would be allowed to continue his career. The glint in Smith’s eye and his warm smile were enough to express his pleasure, both at the news and that he was still held in high-enough esteem by Williams to merit a call more than a decade after parting ways.

The Coach likely picked up his caring attitude for his players from his father, a patient, soft-spoken man who was also a coach. Smith grew up on the sidelines of the football fields, basketball courts, baseball diamonds and tracks where his father coached the Emporia High teams in Kansas. During basketball season young Dean spent most afternoons in the gym and went on all of the road trips.

“My earliest basketball memory is shooting baskets at the other end of the court while they [his father’s team] practiced, Smith told me. “My dad said it would be okay, but said to be sure I was off if they started a fast break. One time I didn’t get off in time, so he ruled that out.” His father also taught him to value each human being, a lesson young Dean took to heart.

Smith would go on to be a three-sport athlete himself: a second baseman in baseball, a guard in basketball, and a quarterback on the football field.. He was a switch-hitter who still admits that baseball was his first love. So much so that he even snuck out of church once so he wouldn’t miss an American Legion game in Abilene. His father didn’t believe in playing ball on Sundays, but he didn’t read Dean the riot act when he returned home. Instead, he calmly sat him down and they struck a deal that Dean could play on Sundays, but not if it interfered with church.

Smith took his athletic talents to the University of Kansas where he was coached in basketball by the legendary Forrest C. “Phog” Allen. In 1952 Dean only came off the bench sparingly, but was a letterman on the national championship team that amassed a 28-3 record. He received his first real coaching experience teaching the offenses and defenses to the football players who finished their season and joined the basketball squad late. Smith studied math and physical education at the University, and it appeared likely that he would follow in his mother’s footsteps and become a teacher. His father insisted that he be accredited to teach high school math when he graduated because it would be harder for schools to find math teachers than physical education instructors.

“I wouldn’t have disliked teaching math,” Smith admitted. “I liked trig identities, but outside of that I probably wouldn¹t have enjoyed math as much as coaching.”

His real dream had been to become a professional athlete and he felt his best chance would be in baseball. He had been named the starting catcher during his sophomore year, but no pro scouts came calling on him in the spring of 1953. Smith had another commitment ahead of him anyway: two years of service in the Air Force. The Korean War had erupted when Smith was in school, and the coaches advised all the athletes to join Air Force ROTC to avoid the draft. In turn, the service stint was a requirement.

As he waited for his orders to come through, Smith played semipro basketball for the National Gypsum Company in Parsons, Kansas, while working a desk job in quality control. Eventually he was shipped out to Germany, where he spent a year playing on an Air Force basketball squad formed to boost morale that was based at Fürstenfeldbruck Air Force Base near Munich. Smith met Major Bob Spear on a trip to France to play a team he coached, and the meeting changed Dean’s life.

Spear was intrigued by the pressure defense used by the 1953 Kansas team Smith played on, so he invited him to his home to talk shop. They became instant friends. Spear soon moved stateside to become the head coach at the Air Force Academy and offered Smith a position as his assistant. Fielding a competitive team at the Air Force Academy was a challenge due to a size limit that required players to be no taller than six feet four. Any bigger and they wouldn’t be able to fit in cockpits. Spear and Smith learned together how to beat teams with bigger and better players, even if that meant inventing new ways of playing.

Smith recalled that one of his teammates at Kansas, Al Kelley, had a habit of leaving his defensive assignment to rush the dribbler if he moved near him. The element of surprise confused the dribbler and sometimes resulted in a steal. Spear implemented the tactic after foul shots and in catch-up situations. (A few years later Smith would perfect it into a full-fledged defense that he called the Run and Jump. In his fifteenth year at UNC the method evolved further into the “Scramble” defense, creating an outright double team that has been adopted by teams across the country.) The duo’s methods worked, and in their second season the team had a record of 17-6. Spear appreciated the contributions Smith made and often encouraged him to hang around experienced coaches to soak up all the knowledge he could about the game. Doing so, Smith found himself at the 1957 NCAA coaches’ convention held during the Final Four in Kansas City, where his alma mater was playing with North Carolina, Michigan State, and San Francisco.

Every year at the Final Four, Coach Spear would room with three old Navy friends and fellow coaches: Frank McGuire of UNC, Ben Carnevale from the Naval Academy, and Denver coach Hoyt Brawner. Smith joined them, but it became a tense time for him. His alma mater lost a heartbreaker in triple overtime to McGuire’s UNC squad, 54-53, and Smith had to endure the entire Carolina team coming to the room to celebrate. When forced to say a few words to the team, Smith congratulated them but told them he hadn’t been rooting for them.

McGuire must have liked Smith’s moxie. The next morning over breakfast McGuire asked him to be his assistant at UNC. Smith agreed to visit Chapel Hill in April of 1958 and immediately fell in love with the “Southern Part of Heaven.” He accepted McGuire’s generous offer of $7,500 a year. Smith would spend three seasons with the confidant New Yorker McGuire, who had a penchant for players from his hometown. The best prospects from New York always seemed to end up at Carolina, prompting Sports Illustrated to dub McGuire’s network of scouts the “Underground Railroad.” Smith tried to introduce the idea of recruiting nationally, but McGuire still felt more comfortable with New Yorkers, whom he felt he understood.

McGuire enjoyed living well and his dining and entertaining habits carried over to his recruiting. At the time, it was legal to do so, as long as the expenses weren’t excessive. That definition was ill defined, however, and in 1960 the UNC basketball program came under investigation by the NCAA. Carolina was found guilty of several violations of “excessive” spending, many of which were dropped on appeal. Regardless, Carolina was placed on probation and banned from the NCAA tournament for one year. Their troubles didn’t end there. After a gambling scandal hit college basketball, the president of the UNC system agreed with NCSU’s chancellor to impose sanctions on both schools. McGuire tired of what he considered unjust treatment and left Carolina in 1961 to coach the NBA’s Philadelphia Warriors. He recommended Smith be his replacement and Chancellor Aycock agreed. At 31 years of age, Dean Smith became the head coach of the University of North Carolina basketball team.

The early years of Smith’s tenure were rocky by Carolina standards, although the teams finished a respectable 8-9, 15-6, and 12-12 his first three seasons. But UNC fans were used to Carolina dominating opponents and Smith was even hung in effigy during his fourth season after three straight losses. Smith responded by sticking to his instincts and continued to schedule tough opponents across the country. He even agreed to play a ten-year series against Kentucky, with six of the games being held in Louisville. An unwise decision by a young coach, Smith admits, even though Carolina won seven of the ten.

He also remained a strict disciplinarian and took his practices very seriously. “I was organized in practices, very much so,” Smith told me. “That required two hours every night to sit down with a practice plan, late at night after watching tape … I think you build your program in practices. If you do a good job teaching, then the game is the final examination and you can sit there and watch.”

Smith’s practices were structured to the minute and reflected his deep-seated belief that basketball was a team sport that depended on proper execution. Drills often emphasized the process, not the final result. He didn’t grade by whether or not a shot went in, but by whether it was the kind of shot the team wanted to take. It’s a practice that is still alive and well at Carolina.

“Matt [Doherty] is doing it now on four-on-four defense work,” Smith said. “He’ll grade winners and losers based on whether they gave up a good shot. If they give up a lay-up that’s terrible, that’s minus five. If a guy [they¹re defending] hits a fade-away jumper from twenty feet and it goes in, they get plus four because that’s the kind of shot you want them to take.” The philosophy of breaking basketball into a process-a series of executions-remained the cornerstone of Smith’s coaching throughout his career. One thing he didn’t emphasize was winning. “If you stick with the process-play hard, play smart, and play together-winning is a by-product,” the Coach asserted. “I think if you talk about winning as the end result too much, it interferes with winning. I tried not to look at the score when I was coaching. Were we playing well? Were we playing hard? Let the score take care of itself.”

The tactic worked and the score did begin to take care of itself. His team’s first big win came his second season when they beat Kentucky on the road. “The win at Kentucky my second year-a big upset, the first big upset-I was so happy I walked back to the hotel with a trainer,” he recalled fondly. Smith understood that having solid basketball fundamentals won games. But he was always interested in teaching more than just good jump shots. He spent time exercising his players minds as well, expanding them to think on a deeper level than memorizing set plays and rotating defenses. Each practice began with a terse phrase with a nugget of inspiration or motivation.

“We had a “Thought for the Day” where we would have something from Kierkegaard or something funny like: We’re on the right track, but we might get run over from behind if we don’t continue to improve,” Smith explained.”Some clever little thing like that. Sometimes they were serious: Accept the things you cannot change, change the things you can.” Each player had to memorize that day’s phrase, and Smith would call on someone to recite it during practice. If the player didn’t know it, the team ran laps. On game days the thought was a constant: Play hard, play smart, play together, and have fun.

“They’re not fun when you’re not executing well though,” Smith was quick to point out. “That goes back to playing smart.”

Fans began to notice and get in on the fun in increasing numbers in the 1960s, changing the face of college basketball forever. The major impetus was the spread of television coverage. No longer were just die-hard sports fans who lived close to a university enjoying games. College basketball became a national pastime and rivalries sprung up between teams that were states apart.

In the early sixties, even in ’71, I remember going to Greensboro and there would only be 3,000 fans for a game against Nebraska, which is unheard of today,” Smith said. “Television changed college basketball. It’s a great game played with a big ball. Not like a game like hockey. It’s hard to see a puck. Plus you can see the faces of basketball players, the emotion. And with that came tremendous interest.”

Another event that galvanized interest in basketball was the 1972 Olympic Games. Since basketball’s introduction into the Olympics, the United States had dominated play in its homegrown sport. But the Soviet Union had fielded strong teams that had an advantage of older players, whereas the United States was still limiting play to amateur athletes. Fueled by the Cold War, the rivalry became intense. In 1972 in Munich, the United States lost the gold medal for the first time in history to the Soviet Union after a series of highly controversial referee calls at the end of the game. The American team was so incensed by the poor officiating that they refused to accept their silver medals.

With the heightened interest in seeing the gold returned to the United States in 1976, Smith was chosen to be the head coach. Bill Guthridge, his assistant at Carolina, and John Thompson from Georgetown rounded out the coaching staff.

Smith understood the international implications of the Games and made a departure from his usual coaching attitude. “In the Olympics I did say, ‘Hey gang, we’re all here just to win.'”

The Olympics appealed to Smith’s coaching psyche. “There were no all-stars, so I kept telling them, ‘We’re doing this as a team and we’re not going to have a First Team All-Olympics or a Second Team All-Olympics, like the First Team and Second Team All-ACC,’ ” Smith said. “And when the gold medal ceremony came, there were all of our guys-all twelve of them-standing up there … that was a special moment.”

The Olympic win was a high point for Smith, but it was also a consummate example of the unreasonable expectations that were placed on the Coach throughout his career. Despite his teams’ consistent, unmatched winning percentage, fans and critics lamented ACC and NCAA tournament losses. Fielding Top Ten teams year after year wasn’t enough. Smith was unfairly held to a higher standard. Only number one was seen as good enough for him and Carolina.

I witnessed the attitudes firsthand as a freshman at UNC in 1986. The ’86-’87 season was a jewel by any standard. Joe Wolf, Kenny Smith, Jeff Lebo, and freshman J.R. Reid-who graced the cover of Sports Illustrated that year under a headline that read “Monster Tot”-led a team that amassed an unheard of 14-0 regular season record in the ACC. Their final record for the year was 32-4. But the losses included both the ACC and NCAA tournaments, to N.C. State by one point in the ACC finals and to Syracuse in the Final Eight by four points.

The criticism and disappointment rang out through the dorms and classrooms across campus. Why couldn’t Smith win the big games with such talented teams? Students were quick to forget the national championship four years earlier. (A win that, more than a decade later, critics still claimed had taken Michael Jordan to win.)

In 1989 I would begin to understand the destructive nature of the win-it-all attitude. At a forum in which Smith answered questions from students, he said with a laugh that what Carolina fans needed was a good eight and twenty season. Smith chuckled when I reminded him of the comment and he quickly noted that he surely said that to students, not boosters. “Everybody always says, ‘Let’s win it all this year,’ and that isn’t being very realistic,” Smith said. “Then if you’re number three in the whole country, you’re down. So maybe I was trying to create less expectations by saying that.”

Smith holds a much more tempered view of expectations. “Every morning you wake up … hmmm, I’m breathing. Feels good. If you have no expectations and you do what you’re supposed to do, then you’re pleasantly surprised … I joked to the alumni groups through the years that I could tell what they think of our chances in the season when they say ‘How are we going to do this year?’ or if they say ‘How are you going to do this year?’ If we’re not supposed to do well, it’s my team then.”

Talking to Smith, one can see that he viewed each year’s group of players as his team. Not as a dictator views his subordinate countrymen, but the way a father looks lovingly upon his family. His players weren’t at his side to help put wins in a column and help him break a record. They were there to learn lessons that stretched far beyond the bounds of basketball, including discipline and the keys to success.

“I’d say the most important thing, with any teacher, is to care,” Smith asserted. “I was talking to Scott May last night, who played for Indiana. And he and Quinn Buckner loved Bob Knight because he was demanding. Now, I might question his motivational techniques, but he was demanding and caring. [Coaches should] go into it for that reason.”

Smith didn’t let winning get in the way of caring about his players either. If star players broke team rules they could be benched for punishment, just like the twelfth man on the team. Otherwise, they wouldn’t learn a lesson. And all senior players appeared in the starting line-up their final regular season game, no matter their talent level. “You wouldn¹t do that if winning was everything,” said Smith.

Undoubtedly, Smith’s caring helped make teams cohesive units, leading to success on the court. Eventually his teams silenced most critics by notching him 13 ACC tournament title wins and a second national championship in 1993. But with the acclaim came fame, praise, and awards, polar opposites of Smith’s personality that was shaped by his father’s early directive to never brag about yourself.

To this day Smith is low-key about his accomplishments, brushing aside compliments as unnecessary. Spending time with him it’s easy to understand why. He is bombarded with flattery the way another might be greeted with a nod and a good morning. Such is the price for being viewed by many as a living legend.

While he could easily be a regular on a talk circuit, Smith refuses to do speeches. “Why I’m asked is not because of me,” Smith explained. “It’s back to what our teams did. I make it very clear that I understand that. People talk about our teams, then somebody says your championship. It wasn’t my championship. It was the team’s championship.”

Despite his humble nature, Smith cherishes the spirit of the honors and has acquiesced and accepted numerous awards. They include an ESPY Award for Courage for desegregating Carolina basketball by putting Charles Scott on the team, the University Award, and being named one of the seven greatest coaches of all time by an elite panel assembled by ABC and ESPN, putting him in the company of Vince Lombardi, John Wooden, and Bear Bryant. .

“The most shocked I was with an award was with that one,” Smith said. “You can¹t possibly say who is the best coach. I think there are hundreds, looking back through the twentieth century … I think it was the top seven that I made, but I would be embarrassed to say that. Knute Rockne was ten or something!”

Smith seemed almost as embarrassed when I mentioned the Hall of Fame. He was honored, of course, with the recognition. But while other players and coaches would laud the accomplishment, Smith didn’t even recall the exact year it had been bestowed upon him.

“I’m not even sure coaches should be in the Hall of Fame,” Smith told me. “When I was inducted in the mid-eighties, I said I questioned it because all we’re doing is thanking our players. Because they’re the ones who did it.”

Smith’s tone changed and he became melancholy for a moment. “I wish I could be in the Hall of Fame as an athlete. I’d like to be in as a major league baseball player. But Cooperstown wasn’t for me.”

The bare truth of the statement was written in his eyes, and I wondered if he’d just alluded to another core reason for his affinity for his players, to why he¹s always cared for them so deeply. Maybe, at heart, Dean Smith is still a Kansas kid pounding the hardwood on a fast break and slapping homeruns to the cheers of the hometown crowd.

Selected biographical information was taken from Dean Smith’s autobiography: A Coach¹s Life, published by Random House.

Coach Smith diagramming a basketball play in the sand.

Dean Smith

Click here to purchase the photographs on this page.

© VisitWilmingtonNC.com™

Editor’s Note: This article appeared in Capturing The Spirit Of The Carolinas.

No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, mirroring, or otherwise, without the prior written permission of the publisher.