America’s General

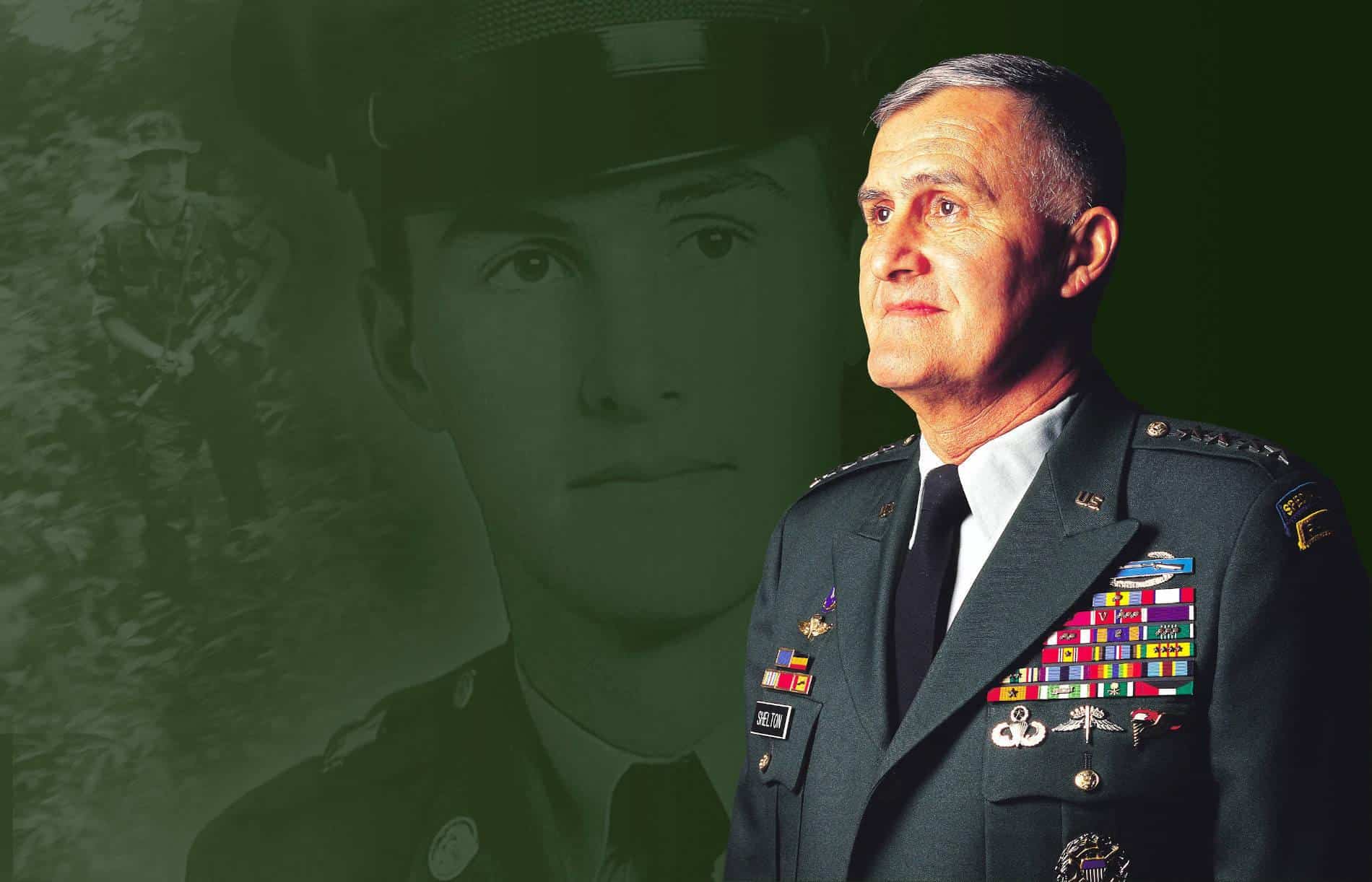

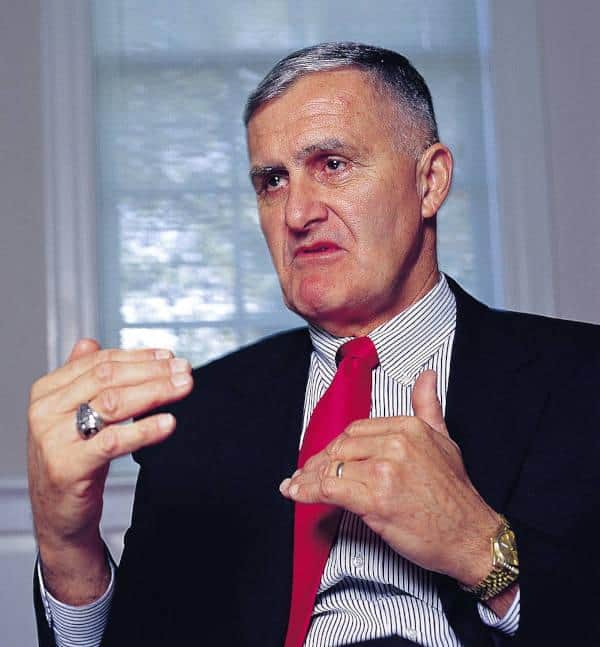

General Henry Hugh Shelton

14th Chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff

Top Military Advisor To Two U.S. Presidents

By Denis Ventriglia. Photography by Brownie Harris.

On November 17, 2001, Capturing The Spirit Of The Carolinas co-publisher and photographer Brownie Harris and editor-at-large Denis Ventriglia met with General Hugh Shelton for a photography session and an interview. The following conversation between General Shelton and Denis Ventriglia took place in the Alumni Memorial Building at General Shelton’s alma mater, North Carolina State University, in Raleigh, North Carolina.

GENERAL HENRY HUGH SHELTON

Henry Hugh Shelton was born on January 2, 1942, in the small town of Tarboro, North Carolina. In 1963, he received a Bachelors Degree in Textiles from North Carolina State University, and was commissioned as a second lieutenant in the Infantry through the Reserve Officer Training Corps on September 19, 1964. For the next thirty-seven years, Hugh Shelton served in a variety of command and staff positions in the United States and Vietnam. In Vietnam, he served two combat tours – the first with the 5th Special Forces Group in 1966 and 1967 (platoon leader), the second with the 173rd Airborne Brigade in 1969 and 1970 (intelligence and operations). He was promoted to Captain on March 19, 1967.

In 1968, he was an executive officer and then S-4 (logistics) with the 11th Battalion, 3rd Training Brigade, U.S. Army Training Center, Fort Jackson, South Carolina.

He served as brigade adjutant and operations officer, deputy division adjutant and infantry battalion executive officer while assigned to the 25th Infantry Division, Fort Shafter, Hawaii, from 1973 through 1977. Shelton became a Major on February 7, 1974.

From 1979 through 1982, Shelton commanded the 3rd Battalion, 60th Infantry in the 9th Infantry Division at Fort Lewis, Washington, and served as the 9th Infantry Division’s chief of staff for operations. He became a Colonel on October 1, 1983.

From 1983 through 1985, then Colonel Shelton commanded the 1st Brigade of the 82nd Airborne Division at Fort Bragg, North Carolina. He was the chief of staff of the 10th Mountain Division (Light Infantry) at Fort Drum, New York from 1985 through 1987. He was selected for promotion to Brigadier General on August 1, 1988.

In 1987, General Shelton began two years as the deputy director for operations in the Operations Directorate of the Joint Chiefs of Staff in Washington, D.C. In 1989, he began a two-year assignment as the assistant division commander for operations of the 101st Airborne Division (Air Assault) at Fort Campbell Kentucky, during which he participated in the liberation of Kuwait during Operation Desert Shield/Storm while deployed in Saudi Arabia.

In May 1991, he was the commanding general of the 82nd Airborne Division at Fort Bragg, North Carolina. On October 1, 1991, General Shelton was promoted to Major General. In June 1993, Shelton was promoted to Lieutenant General and assumed command of the XVIII Airborne Corps at Fort Bragg. In 1994, during his tenure as Corps commander, General Shelton led the United States Joint Task Force that restored democracy in Haiti. On March 1, 1996, he was promoted to General, and became the commander in chief of the U.S. Special Operations Command, at MacDill Air Force Base in Florida, where he was responsible for the readiness of all active duty and reserve component special operations forces of the Army, Navy and Air Force.

General Henry Hugh Shelton became the 14th Chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff on October 1, 1997, and served two two-year terms. His term ended on September 30, 2001, and he remained on active duty through November 1. Since General Shelton’s appointment by President Bill Clinton, U.S. forces have been in heavy demand and have participated in numerous joint operations around the globe. His last task was assisting Commander in Chief George W. Bush in the War on Terrorism during Operation Enduring Freedom.

While Chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff, General Shelton worked on behalf of service members, their families and military retirees by championing a number of quality of life initiatives, including: the largest pay raise in eighteen years, pay table and bonus reform, and critical improvements in both retirement and healthcare programs. He improved the readiness and retention of the current force and crafted Joint Vision 2020 – the road map for the Future Joint Force. General Shelton also established Joint Forces Command to consolidate joint experimentation efforts and guide the transformation of the U.S. armed forces for the 21st Century.

In addition to his N.C. State degree, the general holds a master’s degree in political science from Auburn University, completed Harvard University’s National and International Security Program, and attended the Air Command and Staff College, and the National War College.

General Shelton has received numerous military awards and decorations including four Defense Distinguished Service Medals, two Army Distinguished Service Medals, the two Legion of Merits, the four Bronze Star Medals, one for Valor, and the Purple Heart. He has also been awarded the Combat Infantryman Badge, Joint Chiefs of Staff Identification Badge, Master Parachutist Badge, Military Freefall Badge, Pathfinder Badge, Air Assault Badge, Special Forces Tab, and Ranger Tab. General Shelton has been decorated by sixteen foreign governments including recently being awarded England’s Knight Commander of the Order of the British Empire. His growing list of civilian awards include North Carolina’s highest Award for Public Service, the Eisenhower Award from the Business Executives for National Security, and recognition as National Father of the Year. He was awarded the Congressional Gold Medal in December 2001, passed by the House on December 19 and by the Senate on December 20, 2001.

DENIS VENTRIGLIA: It is Saturday, November 17th, 2001, at 8:55 a.m. We are on the campus of North Carolina State University with General Henry Hugh Shelton. Good morning, General.

GENERAL SHELTON: Good morning, Denis, glad to be here.

Q – I am going to ask you questions about you, your family and career. Let’s begin with your childhood and schools. You were born in Tarboro, North Carolina, in January of 1942. Can you please tell us about your family while growing up, your parents, siblings and what it was like to grow up on the farm.

A – Well, Denis, I was born, as you said, out in Tarboro, North Carolina. I grew up out on a farm owned by my uncle, Henry Gray Shelton, who was a great North Carolinian who served in the North Carolina Senate and ran this large thousand-plus acre farm. I grew up there. My father was a farmer and during my early years he also ran an implement company. He was a Case tractor and implement dealer in addition to farming. Later he got out of the business and farmed full time for the rest of his life. My mother was a school teacher who taught in the Speed Elementary School which I attended for my first eight years. She subsequently retired.

I have two brothers, David and Ben. David is the second oldest son, and Ben is my younger brother. I have a sister named Sarah.

I grew up in this small community, attended Speed Baptist Church, was surrounded by who I think were good, great Americans during that period who were very much a part of what Tom Brokaw has referred to as the greatest generation – very high values, people of great character and integrity. It was a community in which a man’s word was his bond. It was a very safe community. I think for the first 18 years of my life we never even locked the door at night. So it was just a wonderful area to grow up in. It was hard work. I worked on the farm during the summers and did that until I attended North Carolina State. After my eight years at Speed Elementary School, I attended North Edgecombe High School for four years where I played basketball. We did not have a football team. I also played baseball and basically continued to receive the same type of mentoring and teaching and coaching, if you will, from individuals that again, I think, played a very important role in my life because they were focused on character and integrity and good citizenship in addition to academics. In 1959, I enrolled at North Carolina State University, originally majoring in engineering, and then developing a keen interest in textiles. I graduated with a degree in Textile Technology from N.C. State in 1963.

Q – Let’s move into some of your military assignments. Vietnam. Please tell us about your activities during two combat tours in Vietnam, the first with the 5th Special Forces Group in `66-`67, and the second with the 173rd Airborne Brigade in `69-`70.

A – My first tour with the 5th Special Forces Group was a very exciting period. I joined the 5th Group in December of 1966 and was assigned to a Unit known as Project Delta Attachment B-52, 5th Special Forces Group. Project Delta was a long range reconnaissance outfit that was designed to provide strategic intelligence to General Westmoreland, the Commander of all forces in Vietnam, and as such we operated out in no-man’s land where there were no other American units, and it was enemy controlled territory. It was designed to give Westmoreland eyes and ears, for us to find where the enemy was so that we could, in fact, bring in air support on top of the enemy, or if we found large locations, that information would be sent back so that B-52s could fly long range strategic bombing missions against those positions. It was a very, what we call, a hairy operation, a very stressful type of operation. I was there for six months.

Q – Geographically, where was that?

A – Geographically, we operated in the northern part of South Vietnam out along the Laotian border and up along the North Vietnam border out in the triangle area. One day, at the end of that first six months, the Commander of all Special Forces up in the northern region visited our Unit. He had just had an A-Team, which is the basic Special Forces 12-man team, that had a series of posts. I think there were eight or nine of these posts spread throughout the northern part of South Vietnam that basically tried to use indigenous forces known as the Civilian Irregular Defense Group, Vietnamese and Montagnards, to try to control that, to deny those areas to the North Vietnamese and protect the South Vietnamese people that lived there. That day the Commander of one of those camps out on the Laotian border had been relieved of his duty and the Executive Officer had been killed. The Commander of Special Forces needed someone to go in there immediately, and he asked me if I would be willing to go command that team, and I immediately said I would if the current Unit would be willing to let me go. And after a little negotiating, they allowed me to go and take command.

So for the last six months, I commanded this A-Team along with about 600 Civilian Irregular Defense Group members, and we did patrols, and it was a very exciting time. You are out in the middle of nowhere. You are in this little camp. They ran at that time what they called a hit parade in the I-Corps of the northern part of South Vietnam. They listed those eight camps in the intelligence community to say, “These are the ones we anticipate getting hit next,” and for six months I was number one on that hit list – and a lot of that had to do with how effective the North Vietnamese felt these camps were. If you really had been an impediment to their operation, they felt the need to take you out.

I stayed on that for six months. We did not get hit with large forces. We got hit several times with smaller forces. But about a week after I left the camp, it was overrun, and tragically we experienced the loss of some great Americans that were there, but that was an exciting period. I came back for 11 months, and served at Fort Jackson, South Carolina, basically training soldiers, 100 percent of whom were going to Vietnam. They were using the leadership that had been in Vietnam to teach the young recruits what they could anticipate and some tactics, techniques and procedures to basically try to preserve their lives.

I did that for 11 months. I was notified that I was going back again. They said they wanted to send me to Korea for a tour. And I said, “Why Korea? There is no fighting going on in Korea. If I am going overseas and have to leave my family again, why don’t you send me back to Vietnam where the bullets are flying and where I can contribute to help and try to win this war.” And so they very quickly accommodated my request, and I went back to Vietnam for another tour. This time they asked where I wanted to go and I asked for the 173rd Airborne Brigade. It was the first Unit to go into Vietnam. It was an Airborne Unit that had a great reputation and had fought very valiantly at DAK To in the Battle of Hill 875, and I wanted to join that outfit and was allowed to do that, and it turned out to be a great

experience.

I led a Company, about a 155-man Unit. I served as an Intelligence Officer for a Battalion, about an 800-man Unit, and then also had a chance to serve as the Operations Officer of that Unit. So it was a great one-year tour, and I came out of that, out of both tours, feeling that the Americans that served there were doing a tremendous job for this nation, even though, as we all know, the war back at home was not receiving very much support. In fact, popular support was at an all time low. It was a very difficult time for the Armed Forces because the men and women in the Armed Forces then were doing what the nation asked of them, just as they do today in Afghanistan or did in Desert Storm, but there was not an understanding that they were separate from the political issues that were ongoing relating to the Vietnam War, and so the Armed Forces suffered. Morale, I think, plummeted to an all time low, even though the Americans that served there were as great as any Americans that ever wore the uniform.

Q – What political and military mistakes were made by the U.S. government during the Vietnam War, and what should the American people do to make sure those mistakes never happen again?

A – Americans understand when an endeavor is in America’s best national interest, particularly if it is laid out very clearly for them. I think that if the Americans that had traditionally been behind the Armed Forces felt that the government had made the right decisions and was in the process of making the right decisions, and the government had informed the American people as to why this particular conflict was in America’s best interest, the Vietnam War would have had better support.

I think we entered into Vietnam without any clearly laid out objectives. We entered into it without explaining to the American people why it was so important, without ensuring that we built public support for the operations in Vietnam, and certainly throughout the next ten years keeping that public support. I think the real lesson we learned is anytime that you are going to use America’s Armed Forces or any element of America’s national power to include political, diplomatic and economic, that you need the support of the American people as represented by their members of Congress. And if you do not have that as a part of your campaign plan, your master strategy for going into this undertaking, this endeavor, then you will lose the support of the people. And if the people are not supporting it, then why are you

still pursuing it? That came out to me loud and clear.

The second issue we faced there was not using all the elements even of our military power to win. To place artificial restrictions on the use of force, to try to only use force that will be politically popular back home, not to upset anybody’s apple cart, not to use everything in our power to go for the jugular vein, to use technology and our war fighting skills to win and win quickly and decisively, which we did not do in Vietnam, was a great mistake and I think we learned our lesson from that.

Certainly, the military leadership today, your Joint Chiefs of Staff, would not stand by and watch us be put into a position that would be restricted like that again. That’s just not the right thing to do, and I think that you would see them speaking out publicly and loudly that this is not what we ought to be doing.

Q – Do you still have family in North Carolina?

A – Today, my mother, Sarah Shelton, still lives in Speed, North Carolina. She still plays organ in the Speed Baptist Church at the age of 84. My brother David is teaching in North Carolina along with his wife, Claudette, who also teaches. My younger brother, Ben, is a veterinarian in North Carolina, and my sister, Sarah, teaches school in North Carolina.

Q – You received a Bachelor’s Degree in Textiles from N.C. State. Did you have plans to go into the textile industry as a profession?

A – When I graduated from N. C. State in 1963, I firmly intended to go into the textile industry. I interviewed several companies and finally decided that I would accept a job with Riegel Textile Corporation in Ware Shoals, South Carolina. That is the largest plant, I am told, anywhere in the United States that took cotton in one end and turned out finished material on the other end.

However, I had enrolled in the ROTC program at N.C. State. It was mandatory for the first two years in those days, but after two years, I decided that I would pursue the next two years, even though it carried with it a two-year obligation for active duty when you graduated. So I told Riegel that I would have to enter the Service for two years and after that period of time, then I would join them in the textile business.

Immediately after graduating I married my, you might say, childhood sweetheart, Carolyn, whose family had grown up in the Speed area as well. We had gone to grammar school and high school together. As soon as I graduated from State, we were married and I then went to Fort Benning, Georgia, and that started my first two years of active duty.

At the end of those two years, I left the Service and went to work with Regal Textile Corporation. Although I had thoroughly enjoyed the Service and at that point had almost decided I had made a mistake by not making the Service a career, I had made a commitment to Riegel. I had signed a contract with them and I wanted to keep that contract.

Q – At what point did you decide that the U.S. Military would be your career?

A – Well, after working for Riegel about 60 days, I went home one night and told my wife, Carolyn – I said, you know, I like working for Riegal and obviously the financial reward was much greater. But, I said, I really miss the Armed Forces, the duty that I had, the camaraderie. I missed the excitement. In the interim, the Unit I had been in reported to Vietnam. I was getting cards and letters from my friends that were in my Unit in Vietnam, and I guess I had a sense of duty, a sense of having let them down for not staying with them. But I also had had a tremendous two years in terms of the opportunities in business, the challenges in leadership and management that I had been presented, and so I asked her, “What do you think about me applying for a regular Army commission and making the Army a career?” And in her inimitable fashion she said, “Whatever you want to do, I am with you.” I applied for a regular Army commission. About ten months later an individual from Western Union arrived in the office with a telegram from the Army saying, “your application has been approved and you can now proceed to Fort Bragg, North Carolina, for Special Warfare training, and join the Green Berets in Vietnam.”

I was with Riegel for 15 months. It was a great time. It gave me a great appreciation for the corporate world and has reassured me that I made the right decision in terms of what Hugh Shelton wanted to do with his life

Q – How have the values learned in North Carolina helped shape your life and career?

A – I believe that my early childhood days in North Carolina really shaped what I am even today in terms of the emphasis that was placed on character, and the value of integrity, of honesty, of selflessness. That was the type of community I grew up in. It was the type of teaching that I received in school as well as in the church. I think the church played a big role, Speed Baptist Church, in those formative years. It was to some degree the same type of role model that I saw when I came to North Carolina State University, and that, I think, is what we look for in terms of leaders in our Armed Forces. We look for individuals of great character, people of great integrity, that are going to make life and death decisions affecting their fellow Americans; people that are willing to give to public service knowing they are not going to receive a lot of financial compensation, but instead receive a much greater sense of reward for participating in the worthy cause of defending this nation and all that we enjoy as Americans. It all tends to dovetail along the way.

I will never forget when I went in and I was asked to see the General Manager at Riegel. He offered to give me a very healthy increase in pay. I said, “It’s not about money.” He offered another big increase in pay. I said, “It’s really not about money.” He said, “Do you realize that if you go back into the Service you may forfeit two-thirds of your lifetime income potential?” And I looked at him, I said, “Mr. Hardyman, I fully understand that. It’s not about money,” and at that point I think he understood and he said, “Well, then, God bless you, and if you ever want a job in the textile industry again, you come back to Riegel and you¹ve got it.” So I left on a great note, but I think he also learned from that session that there are some people that are motivated by things other than dollars.

Q – Who has had the most impact on your life?

A – That’s a tough question, but I would have to say unequivocally that it is my parents. The values that they instilled in me from the beginning are things that have stayed with me throughout my life, have guided my life, and have allowed me to become who I am today.

Q – What are your rules for success in life?

A – Well, I don’t have a set number of rules as some people do. I would say that rule number one is that character, integrity, and standards are what it is all about for any leader. Leadership is nothing more than the ability to influence people, to make them want to be a part of your team, and to accomplish the goals of the organization. I think people look to leaders to be leaders of integrity, leaders of great character, and unless you have got that from the beginning, the chances of you being successful, particularly in the Armed Forces are pretty, pretty slim.

Rule number two: the harder you work, the luckier you get.

Rule number three: there is no limit as to what you can accomplish if you do not mind who gets credit for it, and that ties into selflessness. It ties into doing what is right for the organization and not worrying about whether you get credit for having led the organization to that success. And rule number four is do unto others as you would have them do unto you, going back to what I was taught early on in church, the Golden Rule. Those are the basic rules that I have lived my life by, and to be candid, the ones that I expect others that I have worked for to live by, and I have been very fortunate in that.

Q – Let’s discuss your wife and children. How did you meet your wife, Carolyn, who is also a native of Edgecombe County, North Carolina?

A – Carolyn and I went to grammar school together and then to high school together, and started dating when I was a junior and she was a sophomore. Upon graduation from high school, I went on to State. When she graduated, she went to work for Carolina Telephone Company in Tarboro as a computer operator. That computer in those days filled the size of a room and she was one of the experts in operating this particular computer. She worked for them while I went to State, and as soon as I graduated from State, we were married and I entered the Army. We have been together now for thirty-eight wonderful years. We have three sons. Our first son, John, was born while I was in Special Forces training at Fort Bragg. The year was 1966, Carolyn was living with her parents at the time back in Speed because I was only going to be there for a matter of weeks, and then en route to Vietnam. One morning I received a call that I had a new son and the Commander I worked for at the time, even though we didn’t have any big events planned for that day, decided that it was not appropriate for me to go visit my son. So I really did not see him until he was 12 days old because I went out immediately on an exercise and did not come back for twelve days. Today he is a Secret Service agent and happens to be with President Bush’s detail. I am very proud of him.

Our second son, Jeffrey, was born while I was in Vietnam on my second tour. I had come home from Vietnam after the first tour and had only been here 11 months when I was notified that I would be going back in about 30 days. And so in 1969 I was back in Vietnam, and one day out in the field in a very awkward position, we were under fire from the North Vietnamese, I was basically pinned down at the time. My radio telephone operator next to me had been hit in the face, and about that time I am trying to call a Medevac for him and at the same time trying to direct my platoons to maneuver against this enemy position. My First Sergeant, who was back a long distance away with a big radio is calling me to tell me that I have a new son, Jeffrey Michael, born on this particular date and weighs this much and the Red Cross has said everything is fine with the mother and the son. And I am screaming at the First Sergeant, “Get off the radio,” and he cannot hear me because I am down on the ground face down with a little short whip antenna on my radio that does not put out much power. He is on a big radio, and he does not hear me tell him to get off, so he starts telling me all this again. And I will never forget thinking, I will never see this son alive because I cannot get through to the First Sergeant to tell him to get off the radio. Well, ultimately he gave up. I was able to maneuver the platoon and fortunately the RTO I referred to fully recovered and came out of it okay. That great son is a North Carolina State graduate and married and today is serving in Afghanistan in Special Operations. He is a MH-60 helicopter pilot, and we are very proud of him.

Q – Is Jeffrey in Afghanistan right now?

A – He is in that region right now, yes. It is hard for me to say where he actually is because he is with Special Operations and I cannot tell you where he specifically is right now, but he is with the guys that are doing the work in Afghanistan right now, yes.

Our third son, Mark, was born in 1978. And Mark today is employed by a defense contractor and lives in Florida. He attended Florida State while we lived down in Florida.

Q – How has Carolyn helped your rise to the top?

A – Carolyn has been a wonderful source of both comfort and inspiration and, of course, has served as both mother and father to our three great sons on numerous occasions while I was in Vietnam for two years, while I was in Desert Storm, while I was doing the Haiti operations as well as numerous exercises of deployment. She has carried a heavy load.

In addition, she has been what I would call a model Commander’s wife. She cares about people. She cares about the young soldiers’ wives. During these very stressful periods when we would have deployments and go off to war zones, Carolyn would run the family support groups and be very active in making sure the families were taken care of. In addition, she supported me by going to all the social functions that we had to go to, and did the entertaining in our home that we had to do, over the last 38 years. I could not have asked for a greater individual to accompany me on this great journey.

Q – How many times has your family moved?

A – Carolyn reminds me in our kitchen where we have a thing that hangs on the wall that has a little house at the top, and the inscription says, “Home is where the Army sends you.” Down below that there is a little heart that hangs for each location that you lived. There are 27 of those hearts now. So it’s been 27 times basically within 37 years.

General Hugh Shelton

Alumni Memorial Building, North Carolina State University

Q – Fort Bragg. At Fort Bragg, you were the Commanding General of the XVIII Airborne Corps in ’93-’96, the Commanding General of the 82nd Airborne Division in ’91-’93, and the Commander of the 1st Brigade of the 82nd Airborne Division in ’83-’85. What were the highlights during those years, and how did it feel to be back home in North Carolina?

A – It felt great to be back home in North Carolina. I had fought hard to get to North Carolina throughout my career, particularly to the 82nd Airborne, which is the Army’s premier division and had not been that successful. I had always had great assignments, but I could never seem to quite swing it. I will never forget the day I was notified that I was going to command the 1st Brigade of the 82nd Airborne because it was so wonderful to be coming back to North Carolina, to be back in the area in which I was raised, to have the opportunity to command in the 82nd Airborne, and get paid on top of that. You just could not ask for it to get any better. It was a wonderful two years commanding in that Brigade.

The only tragic event during that period was the death of my father that occurred in 1984. I did numerous exercises overseas during this period. The Noncommissioned Officer Corps of the 82nd Airborne Division, the sergeants, were so good down there that they made commanding in the 82nd easy. I gained a greater respect for our NCO Corps than at any other time during the previous 18 years of my career because they literally ran the outfit, and their standards were very high. It was a tremendous experience. I left that job thinking, “You know, if I retire tomorrow, this has been a great and rewarding experience and I am totally satisfied with what Hugh Shelton has been able to accomplish in the service of our nation.”

As I was coming out of Desert Storm, having served with the 101st Airborne Division Air Assault, I was notified that I was going back to North Carolina to command the 82nd. That was like a dream come true. By this time, I was a 2-Star and the opportunity to command the division was a very special opportunity for any officer, and to command the 82nd was the ultimate experience.

Commanding the 82nd was rewarding. I had the opportunity to lead the entire division and to know that if the call came to go to war that we would be the first one called. I had been given the funding and the resources to train to make sure we were ready to answer that call. All this was done in a first-class manner which is the dream of every Commander.

Then I was notified that I would get to remain at Fort Bragg and command the XVIII Airborne Corps, which included not only the 82nd but the 101st at Tenth Mountain Division at Fort Drum, New York, and the 24th Division at that time now the 3rd Infantry Division at Fort Stewart, Georgia, a mechanized division – that is America’s premiere contingency corps. If you have got to go to war, that is who you want to go with, as they demonstrated so ably during Desert Storm.

The highlight of commanding the XVIII Airborne Corps was when we were asked to carry out Operation Uphold Democracy in Haiti. This was designed to be a full scale invasion, a joint operation involving all of our Services including Airborne, Marine Corps, and the Coast Guard. I was selected to be the Joint Task Force Commander of that with a nucleus being the XVIII Airborne Corps. To be able to develop a campaign plan and present it to the President, to have him approve it, practice it, and then be told to go execute the plan, was what every commander dreams of doing.

But as we know from history now, as the Airborne was just about an hour or so out from dropping, as the Marines were ready to make the amphibious assault, as the Navy Seals were in the water and their boats were getting ready to hit the targets that I had designated, we were notified that we had a peace agreement with Cedras and he would leave. That we were to stop the invasion and to go in the next morning in an atmosphere of coordination and cooperation, which are not military terms. I had about six hours to put together a new plan and to pull this off as being ready to fight but doing it in a diplomatic manner, which is a real challenge. We were able to do that because of the well trained force I had.

As Dr. Perry, the Secretary of Defense, said later, you know, what we did in Haiti was what you look for in a professional Super Bowl team. We had the ability to do a completely different play from what we had planned. And our team pulled it off because I had great leaders and well trained troops.

Q – Why do you like jumping out of planes?

A – As one individual said one time, “It’s not so much that I like jumping out of planes as it is I like being around people that do.” Airborne units have this very special breed of individual that does this very dangerous and challenging task. They know that they fight like everyone else when they reach the ground, but to know that for a short period of time, as you are put in harm’s way, that you only can rely on your buddy on the left and right and whatever you can drop in with you, leads to a different mind set than it does if you are going to deploy with tanks and artillery and everything else and have everything in place before you have to fight. It creates a very high degree of esprit. It creates a sense of camaraderie in the unit, a sense of bonding that far exceeds anything that I have ever experienced in any other type of unit.

I have made about 300 jumps that are the combat equipment static line jumps like the 82nd Airborne Division does, and a lot of those are at night wearing full combat gear. Then I have about 50 or better free falls, which are jumps done anywhere between 30,000 feet and 10,000 feet with the late openings.

Q – Desert Shield/Desert Storm. While the Assistant Division Commander of the 101st at Fort Campbell, Kentucky, you were sent to liberate Kuwait during Operation Desert Shield/Desert Storm. How would you grade our military’s performance then, and should we have destroyed Saddam Hussein and his military while we were in his neighborhood?

A – I would grade the performance of the soldiers and the units that participated in that as extraordinary. Having said that, I don’t think that we should ignore the fact that it took us a long time to put that force in place. We did not have the strategic lift that we needed, either air or sea, and this was a very demanding operation. Again, to project the force of 500,000 to include a lot of tanks and artillery and armored forces halfway around the world is quite a feat. We are the only nation in the world that could pull that off. Even the Russians, the Soviet Union, in their greatest day could not have done that. They could not even come close, but we did it. In Desert Storm we learned we need to get better. We need to improve our air and sea lift, and improve our forward deployment of some of the heavy stuff that you ought not have to move, and put that in pre-positioned spots in the regions where you may have to fight. We learned the value of precision munitions. In Desert Storm only ten percent of our aircraft could drop precision munitions accurately. When we did the Kosovo operation a year and a half ago, 90 percent of the airplanes dropped precision munitions. These were just a few of the things that came out of Desert Storm that have allowed us to get even better in the intervening years.

But back to Desert Storm, the troops did extraordinarily well. We learned a lot from it, but they performed to standard. We used our air power to basically debilitate the Iraqi forces so that the ground force when it kicked off was able to move very fast to the Euphrates River, and put Saddam in a place where he had to surrender.

I believe with 20/20 hindsight and having had my time as Chairman of the Joint Chiefs occupied by the Iraqis and Saddam Hussein probably 20 percent of my time for the last four years, that it would be very easy to say it was a drastic mistake not to go to Bhagdad. But I do not feel that way. During Desert Storm, the Commander of the 101st, General Binnie Peay, and myself had had a discussion on day number three that it might be time to stop because what had happened is Saddam had pulled out some of his key leaders of his units to preserve them. He had moved them away. And what was left in the field for us to hit were the privates. They were soldiers that were there because they were afraid they would be killed if they left. For the most part they would surrender the minute we would come in contact with them. And I felt that some of the killing that was going on through the air strikes on these units, et cetera, had reached a point where it was not the right thing to do as a humanitarian act. I think the President made the right decision to stop. Today, of course, as Saddam still is a major threat in terms of weapons of mass destruction and continues to defy the international community in terms of living within international norms. It is too bad that he is still there because the Iraqi people deserve better leadership.

Q – Intelligence. What steps would you recommend to the U. S. Military and to the Central Intelligence Agency to improve our intelligence gathering capabilities around the world?

A – The intelligence community has suffered some tremendous losses over the last 15 years particularly in the area of human intelligence. A lot of the things that America finds itself involved in today could be predicted. We could take preventive action if we had human intelligence sources in some of what we call third and fourth tier countries where you have a tremendous amount of unrest and instability that ultimately leads to the conflict that involves the U. S.

But our ability to predict some of that is hampered by the fact that we do not have people that actually are in the country that know what is going on, that are able to tell us, give us a sense of what we ought to be doing to preclude conflict or to enlist our allies in the region to help this particular country and therefore avoid another war. Whether it’s the genocide that took place in Rwanda or what was going on down in Haiti and being able to predict that maybe Cedras was getting ready to overthrow Aristide, it came as a great surprise. The Balkans is another area. So we really do need to improve the human intelligence capabilities of the United States.

I had discussed these issues with both the Secretary and George Tenent, the Director of the CIA, and I know a lot of these issues are being brought, but it’s not really their fault.

As a result of September 11th, we are seeing some great strides being made in that area, and I think that is all for the good. It is too bad that it took September 11th to really get us moving.

We should also continue to improve our work in the international intelligence arena. We receive a tremendous amount of very useful intelligence from other governments around the world; friends and allies we have helped. The stronger we can make that, the more formal we can make some of those relationships, the better off this nation will be in the long term. Finally, we live in a changing world in which we can reduce some of the redundancy, some of the bureaucracy that you find associated with the intelligence community. For example, when we did the Haiti operation, I left most of my intelligence apparatus, the analysis, the collection pieces of it, back at Fort Bragg. We were tied together over the Internet. So I did not have to feed an extra three or 400 people, all the baggage and all the space and all the additional lift that that requires. We can do a lot better today than we have been doing. And it is a matter of using today’s information technology, our IT, to be able to operate with a smaller number of people, disburse it faster, to lower levels without having to have a layering effect all the way down to the Commander in the field.

Q – Let’s move into your tenure as Chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff. You were Chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff from October 1, 1997, through September 30, 2001. Please describe the functions of the Joint Chiefs of Staff and the special role of the Chairman.

A – The Joint Chiefs of Staff serves as a collective body to provide the best military advice to the National Security Council, to the Secretary of Defense, and to the President. It consists of the four Services, Chief of Staff of the Army, Chief of Naval Operations, Chief of Staff of the Air Force, and Commandant of the Marine Corps, and the Vice-Chairman and the Chairman. It is a very powerful group whenever they speak with one voice because it represents, as a minimum normally, close to 200 years of military service to the nation, if not more.

During the Vietnam era there was a lot of parochialism among the Services and a lot of the recommendations from the Joint Chiefs individually about what the right answer was for Vietnam. They did not speak with one voice. The power of the Chairman, who had to present the collective view of the Joint Chiefs, was limited in that if he could not speak as a collective for the Joint Chiefs, as one voice. That made the Joint Chiefs very ineffective, and history shows that during the Vietnam era the Joint Chiefs did not do much to further the cause to correct the things that were wrong militarily with the operation. Each one of them thought his Service had the right answer, and they could not agree on joint strategy.

In 1986, the Goldwater-Nichols Bill recognized this weakness. Goldwater-Nichols recognized that we had too much parochialism in the Armed Forces and was designed to create a joint approach and to use the complementary capabilities of each of our Services in every operation in a way which best fit into the overall campaign plan of the Combatant Commander. It also determined new powers of the Chairman by making the Chairman the principle advisor to the National Security Council, the Secretary of Defense and the President.

The collective body of the Joint Chiefs is a very useful tool. As Chairman, I used that frequently, particularly on any major issue that I was going to be talking to the President or the National Security Council about to get kind of an azimuth check for myself as to whether or not my judgments were in keeping with the way the other members of the team would see it. Sometimes we would have a divergence of opinion, but every time that I would go to the President or to the Secretary of Defense, if I knew that I had dissenting voices in the Joint Chiefs, I would tell the President that, you know, four of the six believe we ought to be doing the following, which is my recommendation. But I do have two and I’ll tell you who they are and why they are concerned and what their opinions are so that he was playing with a full deck. If I had 100 percent concurrence among the Joint Chiefs, I would say my recommendation is the Joint Chiefs are 100 percent in agreement, et cetera.

The Joint Chiefs meet on all key issues. They confer. They form opinions and voice their opinions about the right way ahead for the Armed Forces, and we try to stick to the military lane. Of course, the President has to deal with the political, the economic, the diplomatic, the military, and the international community. But for the Joint Chiefs of Staff, and specifically the Chairman, he makes the recommendation on what is best for America from a military perspective based on the capabilities of our Armed Forces.

Q – Who do you believe is the greatest military strategist in the history of the world?

A – Carl von Clausewitz, the respected Prussian military strategist.

Q – Is there anything that you would like to tell potential adversaries of the United States of America?

A – The United States of America is a great country. It is great because of what we believe in. We believe in free and open societies. We believe in individual liberty. Americans’ beliefs in individual rights and liberties and freedom for our people are clearly spelled out in our Constitution. America is a very compassionate nation. It is one which likes to help people, but America is also a very powerful nation, the most powerful nation in the world today. To potential adversaries I say you need to look at America for what it is.

The United States of America has tremendous Armed Forces. It has capabilities that range from humanitarian operations to fighting a nuclear war, and you ought to think twice before you decide that you are going to take on the United States of America – because you are going to lose. You are going to lose big. You are going to lose your Armed Forces. You are going to lose your nation if that is the will of the American people. So cooperating and existing with the United States is in most nations’ best interests.

On the other hand, I think America has an obligation to understand the formative issues of other nations, and the different cultures of other nations, and we should not try to impose our way as right on them all the time. We should not be unilateralist. We should work to achieve cooperation among nations and be a partner with them while still pursuing our own objectives. I think that is truly the way ahead, particularly in the globalized world that we live in today.

We create a lot of enemies if we are seen as unilateralists with a big stick. I do not think you will find any nation out there today that is going to want to take us on head on, and that is why we have to be concerned about terrorism. It is what the Joint Chiefs have been saying now for the last six or seven years. The asymmetric way of coming at America is the way we can anticipate, the thing we can anticipate in the future, and September 11th is just a very vivid example, but only one example, of a way in which they can come at us. Those are the things we have got to be concerned about for the future.

Q – I understand that you lost your next door neighbor when the plane hit the Pentagon on September 11th. What were your personal and professional feelings after you learned of the loss of life at and the damage to the Pentagon?

A – Well, I had just taken off that morning at 6:30 en route to Hungary and Naples for a NATO meeting and then back into the United Kingdom where I was to be knighted by our great ally, the U. K., and that is something I had really looked forward to. About two hours out, I was notified that an aircraft had run into one of the twin towers. I knew that the weather on the East Coast was crystal clear that morning. I had gotten a weather report just prior to departing and looked at the entire East Coast, and I was not sure then that that was an accident. I could not figure out how that could be, how you could have an accident like that, not on a clear day, not given the confidence in our pilots in commercial airlines and our air traffic control mechanisms.

When I heard that a second plane had just run into it, immediately I said, “Either we have got a terrible software program or we have got a controller that has gone berserk, or we have got a terrorist act, and I think it’s terrorists.” And a few seconds later they told me now we think we¹ve got a car bomb that had gone off at the Pentagon, and at that point I started turning the airplane around. I knew then that had to be terrorists.

And it is a long story, but as I got back, having gotten clearance to fly back into the United States, I saw the smoke as I flew over New York. The whole East Coast had been shut down. NORAD, the North American Air Defense Command, had scrambled at the request of the federal aviation authorities and had launched fighters. The FAA had now shut down all commercial traffic and was not allowing anyone to come back into the U. S. King Abdulla had been trying to come in. I talked to him later, and he had been turned around before he could enter in through Canada en route to the U. S. and sent home because they weren’t going to let someone fly in. I finally got through, through my Vice Chairman, and we had gotten NORAD and the FAA to clear my aircraft. We came back, and as I went over New York, I saw the smoke spiraling up to 10,000 feet as the World Trade Center burned. And I got a more accurate report on what had happened at the Pentagon.

Your first thoughts personally are remorse for those that you know have died. And in the World Trade Center, you know, I thought it would be even greater than it turned out to be. I had concern for the families whose lives would be changed forever by this event. And second, a feeling of wanting to get revenge, wanting to get retribution – the normal emotions that any American would feel for having this heinous act committed. But, from a military perspective, professionally, you know, I cannot think that way. I have to think in terms of what we have to do to defend ourselves from this type of thing. What can we do to go after the organization that did it, and there was no doubt in my mind who had done it. I mean, from day one. There was a matter of opinion that he might have had accomplices in this, and whether or not there had been other nations that were supporting it. I had to get back on the ground and focus on what we need to do now to go after the organization that did this to us. Focus on what we can do to take out this organization, to degrade it, to make it ineffective. My mind started thinking militarily about what my recommendations would be to the Secretary, and to the President as we moved forward.

It was only later that I learned that Tim Maude, my next door neighbor, a Lieutenant General that I had just seen and spoken to while he had been out running in the neighborhood on Sunday morning, was one of the victims of this terrible attack. That’s what went through my mind early on.

Q – For the historical record, can you tell us as much as you can about what you did during the first 24 hours after the attacks and what communications you had with our leaders?

A – I landed back at Andrews Air Force Base. Again, everything on the East Coast was shut down. I was in a 757. The military call it a C-37. It’s one of the four big jets that the Chairman, the Secretary of Defense, the Secretary of State and Vice President use to make official trips. When it touched down, I was amazed at the lack of activity because nothing was going on, but I was also surprised to find 16 District of Columbia police officers with motorcycles and cars there waiting for me to escort me back to the Pentagon. I knew then the tremendous psychological impact that this had had on the City of Washington and it turned out on the Nation.

When I got back to the Pentagon, I went immediately – I didn’t even go in the office – I went immediately out to the site to see exactly how much damage we had physically to the Pentagon. I went back into my office then which was still filled with smoke and the smell of cordite from the explosion and took a look at the current state of where we were communications-wise, computer systems-wise, and found out we were in good shape. We had remained operational throughout that.

We have great systems. We exercise them regularly. Although we had activated the alternate command center underground up in Maryland just in case we got hit again with something, we did not use that. The Pentagon kept operating, and the people in there, even though the smoke was thick at one point, continued to stay at their posts and keep things going.

After that I met with Senator Warner and Senator Levin from the Senate Armed Service Committee who were at the Pentagon and with Secretary Rumsfeld. Then a few minutes later, I found myself standing in front of the cameras for the first news appearance, and my goal there was to reassure the American people that our Armed Forces are in good shape and they are ready to go, and that we will take military action against the perpetrators of this heinous act against our citizens and against the Pentagon. After that, I had a meeting with the Secretary.

The next day I had a meeting with the National Security Council. In the interim, I had reviewed the structure and the targets, if you will, the potential points that we might be able to take action against the Al-Qaeda organization, so that I would be able to discuss that with the National Security Council and ultimately with the President, and then later that afternoon met with President Bush.

Q – How does the American public overcome the fear generated by the September 11 attacks?

A – I think that what we need to understand as Americans is that a lot of the privileges and rights and freedoms that we enjoy as Americans are also the things that make us susceptible to terrorists, but that we have been that way throughout the existence of our Nation. We have one organization that did decide to perpetrate an act of this type and carry it out and that right now, the best defense against this type of an organization is an offense, and that right now you have every federal agency of this government, under the leadership and guidance of President Bush, that are going after this outfit militarily, economically, with information power, diplomatically and politically. We’ve got an international movement that is going against it now.

The ability of them to coordinate and to carry out these operations when they are under this type of pressure is pretty darn slim, and it doesn’t stop in Afghanistan. The thing we need to remember is that just happens to be the outfit that is harboring Osama Bin Laden himself and many of his lieutenants, but he operates out of about 55 other countries including the United States. We have to use every instrument of our power to go after that organization and to take it down to make it ineffective, and we have the capability to do that and we are doing it, and I commend President Bush and his team because they are using all the instruments, even the economic tool, which had been verboten until recently.

So Americans should not feel that they are in any greater danger today than they were on September the 10th. They carried it out, and for that reason you feel much more vulnerable. But we also have a much greater chance now of stopping something of that type because every agency we have in the government is out there trying not only to defend against it but to take it to those who would otherwise carry it out. To some degree, we are safer today than we were on September the 10th by quite a margin.

Q – Under what circumstances is it appropriate for the United States to use nuclear weapons?

A – Well, that gets into personal opinion, but I believe that will always be a judgment call that will have to be made by the President. Our nuclear weapons are a great deterrent, and certainly they are a deterrent against those who own nuclear weapons. You cannot fire a nuclear weapon as a nation state at the United States without us knowing about it instantaneously, and therefore, if you want to find yourself vaporized, that is probably the quickest way to do it.

We have to consider it in the overall scheme of our resources, over all our forces, when it would be appropriate, and I think the best policy the United States can have is the one that it does have. We never tell an adversary what might carry us over the threshold. Would hitting New York City, Chicago, Los Angeles, Raleigh and Atlanta simultaneously with chemicals that killed hundreds of thousands of people, if they could do it, would that mean that if we could identify the perpetrator, a nation state or an organization that we would not – you know – consider the use of some type of a nuclear weapon on them? We have never said that we would not, and we have not said that we would, and I think that is the way it ought to go.

Q – What is your advice to the President and to the Congress regarding the necessity for the national missile defense system?

A – Well, Denis, let me very quickly say up front, one of policies that I adopted early on in my Chairmanship was that I would never discuss publicly what my recommendations were to the President, and I assured him that those would always be between himself and me. If he wanted to share it with someone and said, “Well, the Chairman recommended this,” I would not object. That would be fine.

National missile defense, I think, is something that all Americans ought to be concerned about, because it is a foregone conclusion that we are going to be more susceptible in the future to missile attacks from nations that might act more irresponsibly than Russia or China or India or Pakistan have in the past. When you look at some of those nations today like North Korea, Iran, Syria, and others that may be pursuing a nuclear capability, we see irrationality such as that associated with some of Saddam’s decisions. You just never know what to expect. So if there is going to be a threat, and I think everyone acknowledges there will be sooner rather than later, of a missile coming at us, if we have the technology to stop it, then we need to decide if we want to build a system here in this country that will defend

all Americans against a missile attack from a nation of this type.

First of all, we need to understand this is, as envisioned right now, a limited defense. It won’t stop Russia’s missiles. I mean, those would overwhelm any system that is being envisioned right now, and by the time we field it, it wouldn’t stop China’s missiles with what they have, and the projection of where they are going. But, again, it gets back to that small number that may be in the hands of someone who would act irrationally and not care what happened to his country that you might want to defend against. If there is a threat, and if the technology is there, the third element is, can we afford it? Well, America can afford any defense it wants against anything. It is just a matter of priorities and where we want to put it. I think we ought to pursue the technology. My only concern would be that before we make a decision to deploy it, I think we owe the American people an answer in terms of what it is going to take to do it and what are we talking about in terms of costs because if it is billions and trillions of dollars that it would take, how does that impact on the other forces that America needs to remain a leading power to protect its citizens, and to provide for our economic prosperity, forces that we know are going to be used as they have been in great numbers since the Berlin Wall came down, since the end of the Cold War.

Then acknowledge up front that the missile defense is probably an additive number of dollars above what it takes for us to operate in the world today and maintain our leadership role with today’s Armed Forces. It will be a tremendous fiscal burden on America. Again, if we think it is necessary to do that and if it is the right answer, we ought to do it, but we go into it with our eyes wide open. It goes back to gaining the support of the American people before you go into any operation. I would say this is a rather major undertaking that we need to make sure the American people are behind.

Q – If money were not a factor, what would be your offensive weapons wish list for the U.S. military in the 21st century?

A – The greatest thing that we have had in our inventory today on a conventional war fighting perspective is shooter technology. Shooter technology takes our different national systems of being able to observe and to detect targets and to link them automatically to shooters that can engage instantaneously. Example, if you really do want to eliminate the Al Qaeda organization and you have – let’s say we had 100 percent satellite coverage of Afghanistan, the ability if you picked him up coming out of his cave and getting into a white vehicle to instantaneously link that to a shooter that could react, that is the way of the future. That is where we are headed right now, and we have come light years since Desert Storm.

In allied force operations, we had unmanned vehicles that could pick up targets that could relay immediately to a fighter to put weapons on the target; we want to automate that system in some form or fashion. So I think that is what is going to keep us well ahead. Our ability to use more and more unmanned or unaccompanied vehicles will be also very important and we are proceeding in that manner as we speak.

Q – How can our government protect its citizens against biological, chemical and nuclear attacks?

A – I think the best defense we have is a very strong counter-proliferation program which the Bush Administration is pursuing. We need to improve our own capabilities at the local level in terms of not only detection but the ability to clean up from this type of thing. At the national level, we need to pursue with utmost haste the technology that allows us to detect, to identify, and then to be able to neutralize chemical and biological agents that have been brought upon us. That is where we are headed.

We have seen this coming for quite some time. In 1998, the Armed Forces formed a Joint Task Force for Consequence Management that looks at bringing all the military’s capabilities of this type under one command, so that if New York needs this capability, we can respond immediately. That is the whole purpose behind what we call Homeland Security in the military that we have been working on for three years; we have got a ways to go, but that is being pursued very rapidly now in the aftermath of September 11th.

Q – Today communications through the mass media is instant and global, and propaganda is used by combatants as part of their war efforts. Is there a point at which an American citizen’s criticism of its government’s military action, in the media, crosses over from free speech to treason?

A – I don’t believe so, not in the United States. I believe that Americans have the right to speak whatever is on their minds and that is one of the things that makes this Nation great. It is one of the things that our men and women in Armed Forces are prepared to die for. I think Americans also need to understand that their criticisms in many cases are not helpful to their government. But then again, if they do not agree with what the government is doing, they have a right to speak out. If there becomes a majority, then certainly the government ought to be listening to them. And, of course, you always have a dissenting minority no matter what you do, as I’ve learned over the years, and that is all good. That is part of why we are great.

I believe also that when it comes to the press, the press needs to make sure that they always act responsibly, and that is not always the case. They should report factually. I know a lot of the networks and a lot of the written media have at least a two source rule where if they do not get it from at least two sources, they will not go forward with it. But occasionally even then I believe that we end up with reckless reporting that hurts the government, hurts the nation’s causes, et cetera. Whenever I talk to the press I encourage them to try to act more responsibly.

I know some senior executives that have recently put out memos to their organizations reminding them that they have a requirement to act responsibly and to make sure they double check stories before they run them, particularly if it is going to be damaging to the U. S. efforts. It is a mutual thing. It is a responsibility on behalf of the press. It is a right on behalf of our citizens, and there is a balance that you have to strike in that area. For the most part this Nation does pretty well at it.

Q – What criteria should be met before we put any American lives at risk to establish democracy in another country?

A – I think, first and foremost, we all need to understand that the support of the American people in any operation is very important, and we need to make sure that the operation is one that is going to be in America’s best interest. Secondly, I believe that we need to understand very clearly what our goals and objectives are going in and have an exit strategy for how we plan to come out of it.

Third, we need to understand that a lot of nations have a different view of the type of government they would like to have than America has and trying to impose democracy, as we understand democracy, and as democracy operates in the United States, is not necessarily congruent with some other nations. While they may have democracy, it may be in a different form and, therefore, America should not try to impose its own form on another nation. We need an understanding of what our interests are, support of the American people, an exit strategy, and finally, understanding that we ought to use all elements of our national power, not just the military. The military should be the last instrument we use. Before we use the military, we should have tried our diplomatic, our economic, our political, our informational tools and many others to try to solve the issue. Because when you commit the military, that is the last straw, so to speak, and now you are into a war. You are into a conflict of some type. Once we understand all that, then I think we will be okay.

Q – You have received numerous military awards and decorations. We have time to discuss some of those. Could you please tell us about how you achieved the four Defense Distinguished Service Medals.

A – I have been very fortunate in my career to have been given the opportunity in leading America’s Armed Forces a various levels, to have been at the right place at the right time and have a great team of people around me, great Soldiers, Sailors, Airmen and Marines to carry out the operations and some great officers around me to help me plan and supervise the conduct of those.

I was awarded the Defense Distinguished Service Medal for upholding democracy in the Haiti operation. That was a team effort as everyone witnessed. I just happened to be the head, the head guy who was privileged to command it.

I received the Defense Distinguished Service Medal for my time as the Current Operations Officer in the Joint Staff in the Pentagon, which was a tremendous job. I learned more there than any other job I ever had short of the Chairman, and it was great preparation for being the Chairman. As Chairman, I also received it. And so it’s been a matter of great opportunities, but again a chance to lead some great people and be the head of a great team, and I attribute all of that success to them to be candid.

Q – What did you do to earn the two Army Distinguished Service Medals?

A – One Army Distinguished Service Medal was presented to me for my period of time as the Commander of XVIIIth Airborne Corps.

Q – How about the Legion of Merits?

A – The Legion of Merits was presented when I was the Chief of Staff of the 10th Mountain Division . I was asked to come to Fort Drum, New York, by General Bill Carpenter – All-American from the Military Academy who was selected to lead that Division, one day while I was at Fort Bragg. I had just come back from Bright Star, which was a big operation in the desert, the Egyptian desert, and I still had sand in my boots and all over me, and I got there and there was a message saying please call Bill Carpenter. And I called him up, and I did not know where he was.

So I called him, and I have known him from the past but just briefly. And he said, “I really want you to be my Chief of Staff of the Division,” which is a tremendous honor for a Colonel. It is the best job you can have next to Commander. And I said, “I¹ll take it,” and he said, “But you do not know where I am, do you?” And I said, “No, I don¹t, but you are a great leader and I will come work for you.” And he told me then he was going to be at Fort Drum, New York, and he was going to stand up a Division from scratch, and it was the Tenth Mountain. And I went to Fort Drum with Carolyn and my family and we served there for two years and we built the Division and we built a brand new installation from scratch. It was a tremendous experience and a great opportunity, and I was awarded the Legion of Merits

for that.

Q – How did you earn a Bronze Star Medal for valor?

A – That one came in Vietnam while I was with Special Forces, and we were out on a patrol, myself and one other American, and we had a large number of Vietnamese that were injured as a result of gunfire. We were trying to get a Medevac helicopter into a relatively small area. The Vietnamese, the Viet Cong and the NVA that we were fighting basically had the helicopter pad under observation, and it was getting tough to get the helicopter to land, and we had about five individuals, if we could not get them out, that were going to die.

And so the helicopter [pilot] finally agreed that he would make one run to try to come in, and we got all the injured individuals ready to put on, and the helicopter started landing and myself and the other American were telling the Vietnamese to pick up their injured teammates and get them in the helicopter and the fire was starting to be directed at the helicopter, and the fire was still coming at us, and they were not moving.

I hollered at them to get up and start moving. We have got to get them on the aircraft and then I reached down and picked up one of the wounded individuals and started moving out across the open area to get him to the helicopter to get him out. I guess it embarrassed them, and so they got the other four up and got them moving, and we got them to the helicopter and got them out.

The aircraft took one hit out of all of that amazingly. I would have thought he would have had fifty bullets in him, but he did not. He had one that actually penetrated into a vertical prop. I think he told me he had damage in other places but only one that was critical. But at any rate, I got him on there and later the Vietnamese leader there put me in for a Vietnamese Cross of Gallantry Silver Star, and unbeknownst to me the Americans had put me in for an award. The American went back and wrote me up for an award and then later the Commander surprised me by coming out to my camp and pinning that on me.

Q – How did you earn the Purple Heart?

A – Again, in Special Forces. It was right at twilight. We were going after a North Vietnamese hospital that had Chinese advisors in the hospital. We had a lot of intelligence that said this thing was up on this hill or mountainous area, and we had been moving all day, and it was right at dark. And we made contact up the hill where we thought the hospital should be, and I was trying to get the men – at this time we had mountain guides and troops with us, and it was myself and two other Americans, and we were trying to get them to move, and I got up and started moving forward to try to get them moving.

By this time we had started getting fire up in this area, so we knew we had to be in the right place. We started moving and they were not moving. I ran back and started hollering at them in my broken Montagnard language to come with me and turned around and started going up the hill firing as we moved and then went right into the middle of a pungi stake defense that they had put in. Pungi are very sharp bamboo stakes that normally have human feces on them designed to give you infection immediately, and one of those went through my leg. It went in the front and came out the back at the calf; pretty painful at the time. I was able to reach down and cut it off and then got up and kept them moving.

Later one of the other Americans who happened to be a medic that was with me, one of my Special Forces teammates, took it out and said, “We have got to get you back to the hospital,” but by that time we had seized this thing. We still had a lot of NVA in the area, and I was not about to leave them up there, not under those circumstances. And so I continued to call back for some air strikes to come in, and later the next day in the afternoon when finally the NVA had pulled out of the area and we had the place under our control, I finally got on a helicopter and flew back to Denang for medical treatment from the doctor.

Q – Retirement. What will you miss most about military life?

A – There is no question I will miss the close camaraderie that you have with individuals that you have either shared danger with or know that the potential for sharing danger with may be right around the corner, maybe tomorrow. In the military, you deal with people of great character and integrity in a very closely knit organization, and that will be missed.

Q – What are your plans for retirement?

A – I am still in the process of trying to sort through a number of opportunities. One thing is for sure my roots are here in North Carolina. I am indebted to the great North Carolina State University for what it has done for me over the years. I will be a member of the University in some shape or fashion. And then there are other things that I am taking a look at from boards to potentially being a part of a corporation, and that’s still evolving.

I am considering being a commentator for one of the networks. I have been contacted about a book. I have not made a final decision on that, yet. And so it looks like it is going to still be a pretty busy period of time in my life, but one in which I hope I can give back to this great state and specifically to North Carolina State University.

Q – You have already given a great deal, General.

A – Thank you.

Q – General, what do you want inscribed on your tombstone?

A – I think, Hugh Shelton, Soldier.

DENIS VENTRIGLIA: Thank you, very much, General.

GENERAL SHELTON: Thank you. It has been my pleasure.

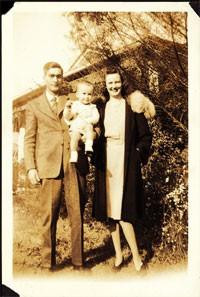

1943. General Shelton, age 1 with father Hugh Shelton, Edgecombe County farmer and mother, Patsy Shelton, N.C. public school teacher for 35 years.

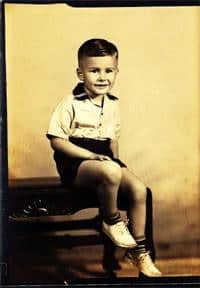

General Shelton, age 3, Speed, North Carolina.

Captain Shelton on patrol in Vietnam in 1966 while assigned to the 5th Special Forces Group Force (Green Beret).

General Shelton makes last military free fall parachute jump from 15,000 ft. at Fort Bragg, N.C. in September 2001. Dept. of Defense photograph.

Secretary of Defense Donald H. Rumsfeld (center) conducts a news briefing on the terrorist attacks on the Pentagon and the World Trade Center on September 11, 2001. Army Secretary Thomas White (left), Chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff General H. Hugh Shelton, Senator John Warner, R-VA (2nd. from right), and Senator Carl Levin, D-MI (right), joined Rumsfeld in the briefing in the Pentagon. Dept. of Defense photograph by Helene C. Stikkel.

President George W. Bush and General Shelton in the White House Situation Room. January 30, 2001. Official White House Photograph.

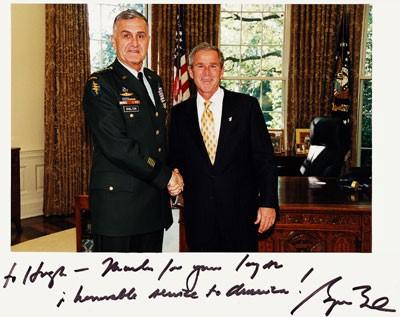

President George W. Bush congratulating General Shelton on his distinguished service in the Oval Office. September 2001. Official White House Photograph.

VisitWilmingtonNC.com™

© VisitWilmingtonNC.com™

Editor’s Note: This article appeared in Capturing The Spirit Of The Carolinas (2002).

No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, mirroring, or otherwise, without the prior written permission of the publisher.

Notwithstanding the foregoing, the publisher hereby grants students and teachers at accredited nonprofit institutions the use of the above “Interview With General Henry Hugh Shelton” and only in its entirety, for noncommercial face-to-face teaching activities to include digital transmissions under 17 U.S. Code § 110. This grant extends to U.S. military institutions and ROTC programs.